To narrate the ups and downs of the history of the seal also means to narrate the history of our sea. A history marked by periods of exploitation and domination, by episodes of degradation and destruction, but also by opportunities for resilience and hope. The knowledge that seals, carnivorous mammals that can weigh up to three quintals and are perfectly adapted to life in the liquid element, still manage to survive next to some of the best-known and most crowded tourist resorts in the Mare Nostrum, arouses the same wonder one felt as a child leafing through illustrated natural history books. With our commitment and our images, we dream of asking people to slow down for a moment and finally pay attention to the beauty, complexity and inescapability of nature and, in this case, of a sea that is not just a holiday destination or the scene of the dramas of modernity, but a real hotspot of biodiversity of global importance.

Editor’s note: This text as well as the following ones are excerpts from the photographic book “Out of the Blue — The Monk Seal in the Mediterranean” by Marco Colombo, Bruno D’Amicis and Ugo Mellone, cofounders of the collective The Wild Line.

Virtually invisible to the gaze of most people, these animals move carefully in the twilight hours, abandoning the safety of their sea caves when they feel secure. It happens in a handful of lucky and secret places, between the Ionian, Aegean and more eastern areas, at certain times of the day. There, it is still possible to experience the thrill of seeing, all of a sudden, the water ripple and a large, round, shiny head, two lively eyes and a snout adorned with long whiskers emerge, to observe their surroundings with curiosity.

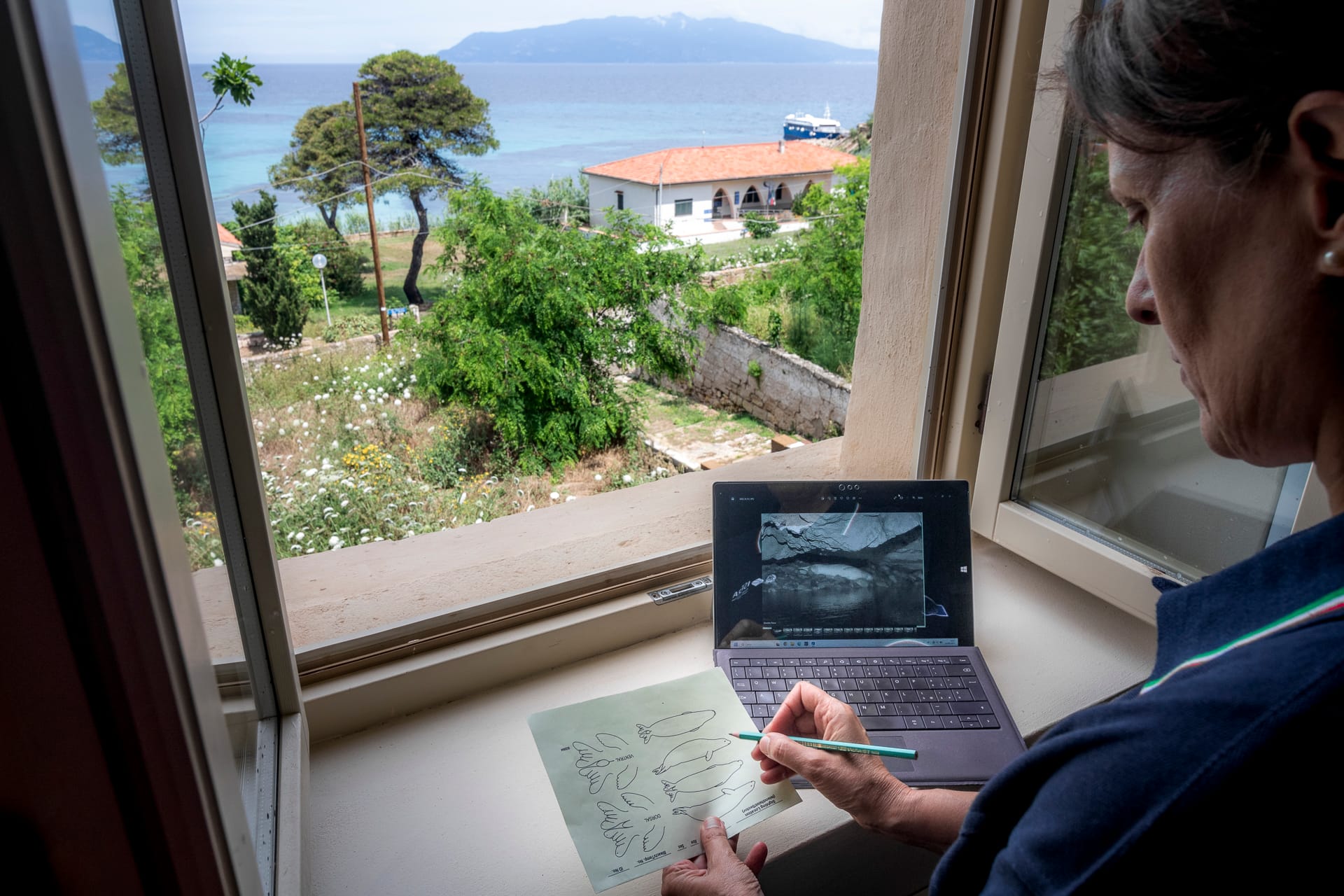

“The Mediterranean monk seal is the rarest seal species in the world and the most endangered marine mammal in Europe. Today the estimated population consists of approximately 800 individuals in total, of which about 400 live in the Mediterranean Basin,” writes Aliki Panou, a conservationist and monk seal expert from the Greek non-governmental organization Archipelagos, in the photo book.

Its former distribution range extended throughout the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Atlantic coasts of northwestern Africa including the Canary Islands, Madeira and the Azores, she adds. Homer describes vast herds of seals lying on the beaches, while Proteus, a sea god, would come out of the sea daily to count them in groups.

Today, however, these charming animals have disappeared from extensive regions of their former range. About half of the remaining world population lives in Greek waters along with smaller populations in Turkey and Cyprus.

“When the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) launched the first conservation programme for the Mediterranean in the late 1970s, the monk seal immediately became one of the main topics of its study and intervention campaign,” writes Luigi Boitani from Monk Seal Alliance. “Early research suggested a very limited number of seals, which remained in small groups, distant from each other. They were under severe threat by three main factors: fishermen who still shot them dead, because they were damaging their nets and eating the fish stuck in them; the reduction of food resources due to overfishing, often even with the use of explosives; and anthropic disturbance due to the dizzying expansion of human presence along the coasts.”

At the first conference on monk seal conservation in Rhodes in 1978, most of the (few) experts agreed on the prediction that the species would be totally extinct within a few years.

“Fortunately, we (I was also one of them) were wrong and the seal is still with us, it actually seems to be slightly increasing in numbers and distribution range,” Boitani adds.

In Italy, observations of this species validated by the Italian Environmental Agency (ISPRA) over the last 25 years, concern almost all the geographical areas of the historical range, state Giulia Mo and Sabrina Agnesi, biologists working at ISPRA.

“While at the beginning of this century validated observations concerned three to five locations per year, in recent years the number of reports has increased considerably, and the involved locations doubled,” the two researchers write.

“The numerous and repeated sightings in Puglia, the smaller islands of Sicily, Sardinia and the Tuscan Archipelago, as well as the evidence of long-term presence recorded through the monitoring of a number of caves in the Aegadian Islands, suggest that the species' attending in these areas is not entirely random, but rather more or less regular.”

The current data, then, show a potential for recolonization in a large part of Italy's historical range. The availability of large stretches of rocky coastline with caves, which are undisturbed for a good part of the year (especially on certain islands) and easily reached by seals from Greece, could indeed favor the recolonization process. However, Mo and Agnesi remind, the main pressures threatening the species must be controlled: “Although deliberate killing may have diminished as a result of increasing welfare and environmental awareness, the disturbance caused by tourist activities in the vicinity of caves should be reduced.”

“The monk seal, like all wildlife,” says Monk Seal Alliance’s Luigi Boitani, “is protected especially by leaving it alone, far from our intrusiveness.”

Cover image: "In the reflections of the early morning, the blue silhouette of a seal slips silently over the colours of a shallow seabed. Regardless of its size, underwater this animal becomes one with the liquid medium" (Bruno D'Amicis).

THE WILD LINE

This multimedia project by Marco Colombo, Bruno D'Amicis and Ugo Mellone stems from the need to celebrate the stunning variety of species, habitats and landscapes which are featured in this wonderful region of the planet, without forgetting to assess the human impact which undermines their long term survival. And this to raise awareness about the essential challenges we need to face to preserve the Mediterranean diversity for the future.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in April.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. We put a lot of time and love into making Lapilli+, so we think it's fair to ask less than the cost of a coffee for it. Please switch to the Lapilli Premium plan here; it includes a free two-month trial.

Lapilli+ is a monthly newsletter with original (or selected) content about the Mediterranean and its environment curated by Magma. Here you can read Magma's manifesto.