Most of this month’s Lapilli is dedicated to Storm Daniel, which first caused floods in the region of Thessaly in Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey, and then as a Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone, also known as Medicane, wreaked havoc in Libya causing what is considered one of the worst flash floods — a specific type of flooding that occurs within a few hours of a precipitation event — in recent history. Medicanes are nothing new. But, according to the latest assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), they are expected to become less frequent but more intense given the rising temperatures.

And that’s not all. In this newsletter, we also look into an invasive species of ant that might be spreading throughout the Mediterranean, the ways climate change is affecting grape harvesting in Italy and oil production in Spain, people mourning the death of glaciers and air pollution in Europe. Hope you’ll enjoy it and have a good read!

Note one: This is the first Lapilli brought to you in English but not all the articles linked below are in English as we try to read from a diverse set of sources from countries across the Mediterranean. But you can translate all of the articles we’ve linked using Chrome or another web tool.

Note two: This month, we are sending our premium newsletter, Lapilli+, to all of our subscribers. The upcoming issue will delve into climate change seen through photography. Stay tuned!

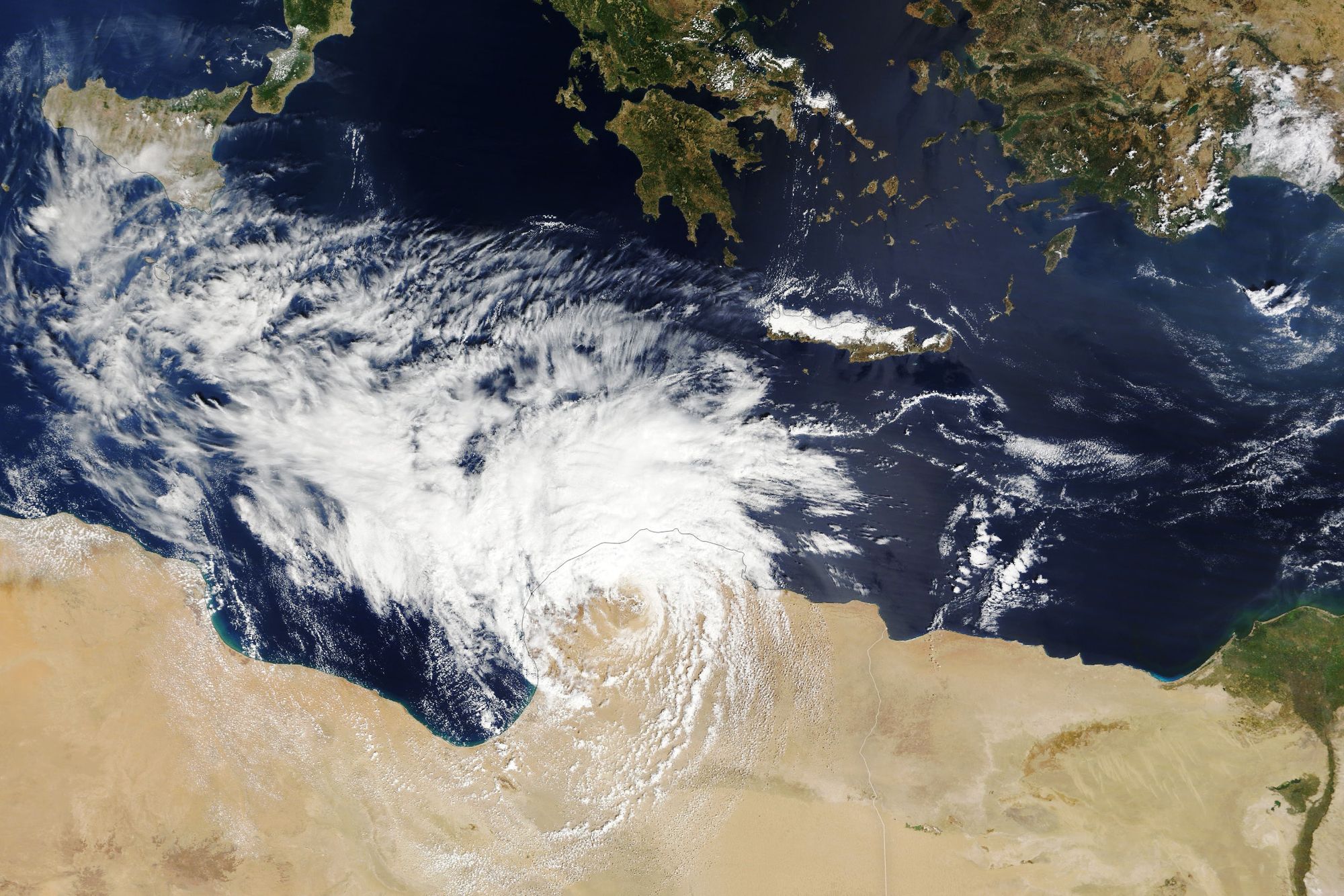

Medicane wreaked havoc in Libya. In early September several countries across the Mediterranean faced intense flooding. The first to be hit was Spain (Reuters). A few days later, a large storm named Daniel swept through Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece and then moved south assuming the characteristics of a Medicane before reaching the northern shores of Libya. A Medicane is a storm happening in the Mediterranean (‘Medi’) that behaves like a tropical cyclone or hurricane (‘cane’). Compared to their tropical peers, Medicanes are smaller in size and with shorter life spans. Like a tropical hurricane, they bring strong winds, big waves and lots and lots of rain (The Guardian).

Greece and Libya have been the most affected by the storm. After a summer of deadly wildfires and record-breaking heat waves, Greece, in particular the central region of Thessaly, had to endure extraordinary amounts of rain: In some parts of Thessaly, 650 millimeters (more than 25 inches) of rain fell in 13 hours. To put that in perspective, 400 millimeters (more than 15 inches) of rain falls annually in Athens (The New York Times).

Scientists say that as water temperatures rise in the Mediterranean, so does the intensity of these Medicanes (La Repubblica via MSN). The World Weather Attribution initiative also confirmed the link between the heavy rainfalls of early September in Spain, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey and Libya with rising temperatures, and estimated that without human-induced climate change, these events would have been less intense and with a longer return period, or average time interval before occurring again.

Within this context, Libya faced what is likely to be its worst flash flood on record. On September 10, Storm Daniel dumped unprecedented amounts of rain on the northeastern part of the country, flooding large areas and generating a flash flood that destroyed 25 percent of the city of Derna, in Cyrenaica. The city sits right next to the Wadi Derna, a river that remains dry for most of the year. But on the night of September 11, the Wadi Derna riverbed filled with a huge amount of water. Under the stream’s pressure, a dam collapsed and then a second dam, which was much closer to the city, burst as well, releasing 30 million cubic meters of water and debris that destroyed everything in its path. In the immediate aftermath, the death toll amounted to more than 11,000 people, and more than 10,000 people were reported missing.

A combination of factors made what happened in Derna so destructive. First, there was an unprecedented amount of rain. In three days the area received more than 100 millimeters (3.9 inches) of rain compared to a monthly average of 1.5 millimeters (0.06 inches). The Wadi Derna geography was also a factor, acting like a water cannon pointed towards the city. The collapse of two dams meant that a wall of water 3 to 7 meters (9.8 to 23 feet) high, full of debris and large pieces of rock and cement, swept through the city. All of this happened at night, when most people were asleep in their homes.

To understand the scale of what happened and how it happened, we suggest reading this BBC report: Why damage to Derna was so catastrophic. The Guardian also published a series of images showing the Libyan city before and after the flood. Al Jazeera investigated the reasons two dams built in the '70s had no chance of withstanding the force of the water. The Copernicus satellite image service published an image showing the extent of the floods in Libya on X, formerly known as Twitter. And to better understand what Derna represents for Libyan culture, we suggest this article from The New York Times.

Derna holds a lesson for all the countries in the Mediterranean. When an intense storm turbo-charged by climate change meets poor land management, a lack of mitigation and adaptation infrastructure, and a nation divided into rivaling factions with no effective alert system or emergency team, the consequences are devastating (The Atlantic).

Mediterranean crops’ meager harvest. September means grape harvest season in Italy but production is 12 percent lower than last year’s and climate change might have something to do with it. According to experts and sector organizations, erratic climatic patterns have had a negative impact on production levels. After two years of drought, the first eight months of 2023 saw 70 percent more days of rain than the previous year. This increased amount of rain triggered the proliferation of a fungal disease named plasmopara viticola, better known as downy mildew, that reduces vines’ productivity (RFI).

In the past few years, droughts and heat waves have also affected oil production levels, mainly in Spain but also in Greece, Italy and Portugal, as well as Turkey and Morocco (The Guardian).

And in case you are wondering, our cover image portrays an olive tree trunk.

Where the earth shakes. Two more pieces of news have little to do with climate change but a lot to do with the Mediterranean. On September 8, Morocco was hit by its strongest earthquake in 60 years, which caused nearly 3,000 deaths and destroyed many villages in the High Atlas mountains around Marrakesh (The New York Times).

Also, the area around Naples, namely Campi Flegrei, keeps shaking. After a 4.2 earthquake recently hit the area, the strongest earthquake in 40 years (ANSA), another one occurred a few days later reaching 4.0 in magnitude (CNN). The city of Naples sits between Mount Vesuvius, an active volcano that has been dormant since 1944, and Campi Flegrei, a large caldera known for its bradyseism, the slow rise and fall of the earth's surface. Scientists fear that sooner or later new volcanic activity, either from the Vesuvius itself or from Campi Flegrei, will occur in the middle of one of Europe’s densest metropolitan cities and that the evacuation plan in place won’t be enough to mitigate this eventuality (Reuters). On the threats that this super volcano poses today and scientists’ most recent concerns, we suggest reading Agostino Petroni's comprehensive feature on Undark.

Glacier mourning. The first funeral of a glacier happened in Iceland in 2019. The New Yorker published a long story about it. The trend hasn’t stopped there. Early in September, on the French Alps, a group of people reunited to bid farewell to the Sarenne Glacier. In the same days, a similar event occurred along Austria’s largest glacier, the Pasterze. Glaciers are actually declared dead when their ice is so thin that they stop moving, growing and evolving. According to the Swiss Academy of Sciences, in the last two years, Swiss glaciers have lost 10 percent of their volume. The funeral is a way to elaborate on the consequences of climate change and to bid farewell to beloved natural environments that are disappearing, offering people an opportunity for grief and closure. Funerals therefore can help raise awareness, bring acceptance and promote preventative actions (The Guardian).

A beekeeper’s loss to wildfire. Talking of environmental emotions, a powerful feature by Stefania D’Ignoti for Al Jazeera helps readers connect with the sorrow of a Sicilian beekeeper who lost not just his home but also his job to the wildfires that surrounded the city of Palermo in July. His story is a poignant example of eco-grief and the personal costs of climate change.

Red fire ants and other invasive species. In a recent study published in Current Biology, scientists identified 88 nests of red fire ants, also known as Solenopsis invicta, for the first time, near Syracuse, Sicily. This invasive species is native to South America and has been spreading across the globe for quite some time. They are considered quite damaging because they attack crops, infest cars and electrical equipment and tend to displace native ants. This is the first time this ant species has been observed in the wild in Europe. They love warm weather, and port cities along the shore of the Mediterranean are particularly suited for them to thrive (The Guardian).

As one of the most destructive and the fifth most costly invasive species in the world, the red fire ant well exemplifies the huge threat non-native species pose to biodiversity, an issue that is often neglected until it’s too late. A new extensive report issued by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) sheds light on the problem and suggests solutions. The report also provides some numbers: 37,000 alien species have been introduced by humans where they don’t belong; 3,500 of them are harmful to biodiversity and ecosystems, costing the global economy $423 billion in 2019 alone, a figure that has quadrupled every decade since 1970. Yet, many measures can be taken to prevent and control alien invasive species, including ecosystem restoration.

But, in Italy, the most prominent invasive species this past summer was still the Atlantic blue crab. Countless stories appeared about this creature, which is now a mainstay on many Mediterranean shores. Not to brag, but our Guia Baggi wrote about it when it wasn’t such a hot topic yet (Mongabay). Recently, The New York Times went to visit one of the towns most affected by this crustacean, Goro in Emilia-Romagna. The local economy revolves around the cultivation of clams — another invasive species that was purposely imported from the Philippines in the '80s — that are now being preyed upon by blue crabs. The town is fighting to save the clams while struggling to make the ubiquitous blue crab a profitable product.

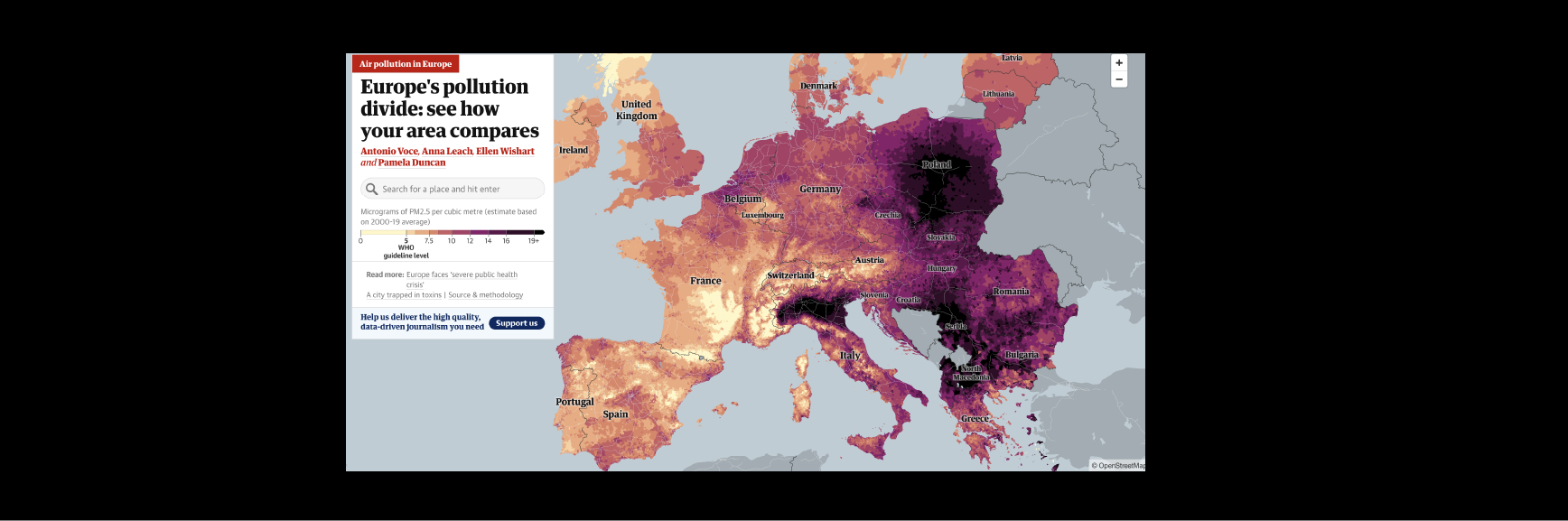

How polluted is the air you breathe? A recent investigation by The Guardian revealed that almost all of the people living in Europe are breathing air containing dangerous levels of pollution. The British newspaper analyzed data from more than 1,400 ground monitoring stations and found that 98 percent of people live in areas with highly damaging fine-particulate pollution that exceed World Health Organization guidelines. An interactive map allows readers to explore the worst-hit areas of the continent (The Guardian).

GUGLIELMO MATTIOLI

As a multimedia producer, he has contributed to innovative projects using virtual reality, photogrammetry, and live video for The New York Times. In a past life, he was an architect and an urban planner, and many of the stories he produces today are about the built environment and design. He has worked with publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, and National Geographic. He has been living and working in New York City for almost 10 years.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in November or in two weeks with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma. Here you can read Magma's manifesto.