- by Bernardo Álvarez-Villar

- This piece has been published in conjunction with Voxeurop.

LOPERA, Spain — Manuel Cabezas grew up surrounded by olive trees. Like every other family in the Andalusian village of Lopera in southern Spain, his parents, grandparents and great-grandparents had taught him that this iconic Mediterranean crop was the most valuable investment he could make. So, with retirement in mind, he used his savings to buy two and a half hectares of land on which to plant 400 olive trees.

“Here, we invest in what we know,” he says. “Not in flats or investment plans we don’t understand.”

However, Cabezas is now worried that his investment and efforts may have been in vain. Like dozens of other farmers and small landowners in the area, he received a letter last summer [in 2024] from the Junta de Andalucía (the regional government), informing him that his land was to be expropriated. This is because Greenalia, a Spanish renewable energy company with investments in several European countries and the United States, plans to build up to seven photovoltaic parks on the site of the olive groves — a project that the Junta de Andalucía has declared to be of public interest due to its contribution to the energy transition.

The press office of the Delegation of Economy and Industry in Jaén, which is part of the regional government, informed us that ‘the Electricity Sector Law, which applies throughout Spain, obliges regional administrations to process applications for a Declaration of Public Utility (expropriations) for electricity installations when the promoter and the owner cannot reach an agreement’. Of the total number of renewable energy projects processed by the Andalusian regional government in recent years, only 0.88 percent have required a declaration of public utility.

Spain is moving away from fossil fuels faster than many other EU countries and accelerating its path towards climate neutrality by 2050 by switching to its abundant renewable resources, particularly wind and solar power. According to the state-owned company Red Eléctrica, nearly 57 percent of the country’s energy consumption came from renewable sources in 2024. This demonstrates Spain’s strong commitment to reducing climate-altering emissions in line with EU climate goals. Solar energy consumption rose by 19 percent over the last year alone. However, the boom in large-scale solar projects may have a negative impact on rural communities, particularly in Andalusia, where most of Spain’s olive oil is produced.

“Nobody cares about us,” says María Mena, a Loperana who comes from a long line of olive growers. “The energy they are going to produce is not for Lopera.” But the land is cheaper here, she concludes.

Greenalia’s plan involves transforming approximately 1,000 hectares of cultivated land into solar parks, each producing no more than 50 megawatts of installed power. The aim is to collectively cover the energy consumption of 164,000 households. Another company, FRV Arroyadas, is also planning a solar project in the area. However, according to data from the Spanish energy distribution company Endesa, Lopera’s population of less than 4,000 people consumed less than 10 megawatts per hour throughout 2023. This has led local residents to question whether the energy generated by such large installations will benefit larger urban centers more than their own small community.

Under Spanish law, solar projects below 50 megawatts are subject only to regional control, thus avoiding oversight by the Ministry of Ecological Transition. Furthermore, Andalusia introduced legislation in 2021 that expedites the approval of such projects, particularly those deemed to be of public interest.

Carmen Torres Bellido, the mayor of Lopera, said that the municipality was not prepared for the arrival of the solar farms. “We had heard for some time that solar panels were going to be installed here,” she said. However, she added that the process had not been carried out fairly or transparently. “They say this is in the public interest, but it’s bad for us,” said María Mena. “It is ruining our community to enrich big companies.” Greenalia never replied to our requests for comment.

As in other rural areas across central and southern Spain, such as Cartaojal or Zamora, where similar projects have been discussed, opposition to these projects is widespread in Lopera. Many locals fear that these projects would damage the local economy, accelerating depopulation and destroying the landscape. They would also deteriorate the soil and consume millions of liters of water per year to clean the panels in a region that is experiencing increasingly frequent droughts.

“The problem with current photovoltaic projects is that they are getting bigger and therefore having a greater impact on the landscape, agricultural resources and soil,” says Matías F. Mérida, a geographer at the University of Málaga who has studied the environmental impact of this type of infrastructure on the landscape. “Rather than being integrated into the area, these installations replace one landscape and land use with another. Fertile land, cultural heritage and centuries of tradition are being wiped out by these giant installations.”

In Lopera, Greenalia has already uprooted thousands of olive trees, some of which are centuries old, to make way for solar panels. Even a subcontracted worker involved in the removals, who requested anonymity, expressed his distress. “For those of us from here, it’s especially painful to watch because we know how much effort it takes for these trees to grow,” he said.

Anyone walking or driving through the north-eastern part of the city will see the vast expanse of land where olive trees once stood. Now, it is a wasteland scattered with parched, uprooted trunks. Mena burst into tears as she watched the centuries-old trees being torn from the soil.

“We cannot let them die,” says María Josefa Palomo, another farmer affected by the expropriations. “For us, they are like neighbors — you go outside and there they are.”

Beyond the emotional toll, many fear that this shift in land use could render once-fertile fields barren and accelerate desertification. “The soil compaction required for installing solar panels implies a loss of nutrients and physical properties,” says the geographer Matías F. Mérida. “As the soils are left without vegetation cover, rainfall generates runoff and contributes to erosion, causing the loss of the most superficial layers, which are the richest in organic matter. Whether or not this is reversible depends on many factors.”

Farmers also discuss this issue when they gather at the village café at the end of the day to voice their frustrations. “They bring in machines to compact the soil and strip away the fertile topsoil,” says Juan Campos, another Loperano who, like Cabezas and Palomo, is facing expropriation. “In ten seconds, they tear down what we’ve spent 40 years building.”

For Lopera’s farmers, losing their olive groves is not just an economic blow; it also means giving up an age-old tradition and the proud identity of this area.

Javier Calvente, the Economy and Industry delegate at the provincial delegation of the regional government, denies that “the landscape of Andalusia is changing and that an emblematic industry such as olive growing is losing its relevance.” He provides data to contextualize the situation: “In Andalusia, the surface area of olive groves increased by 27,000 hectares between 2018 and 2024, while in Jaén it increased by around 5,000 hectares in that period.”

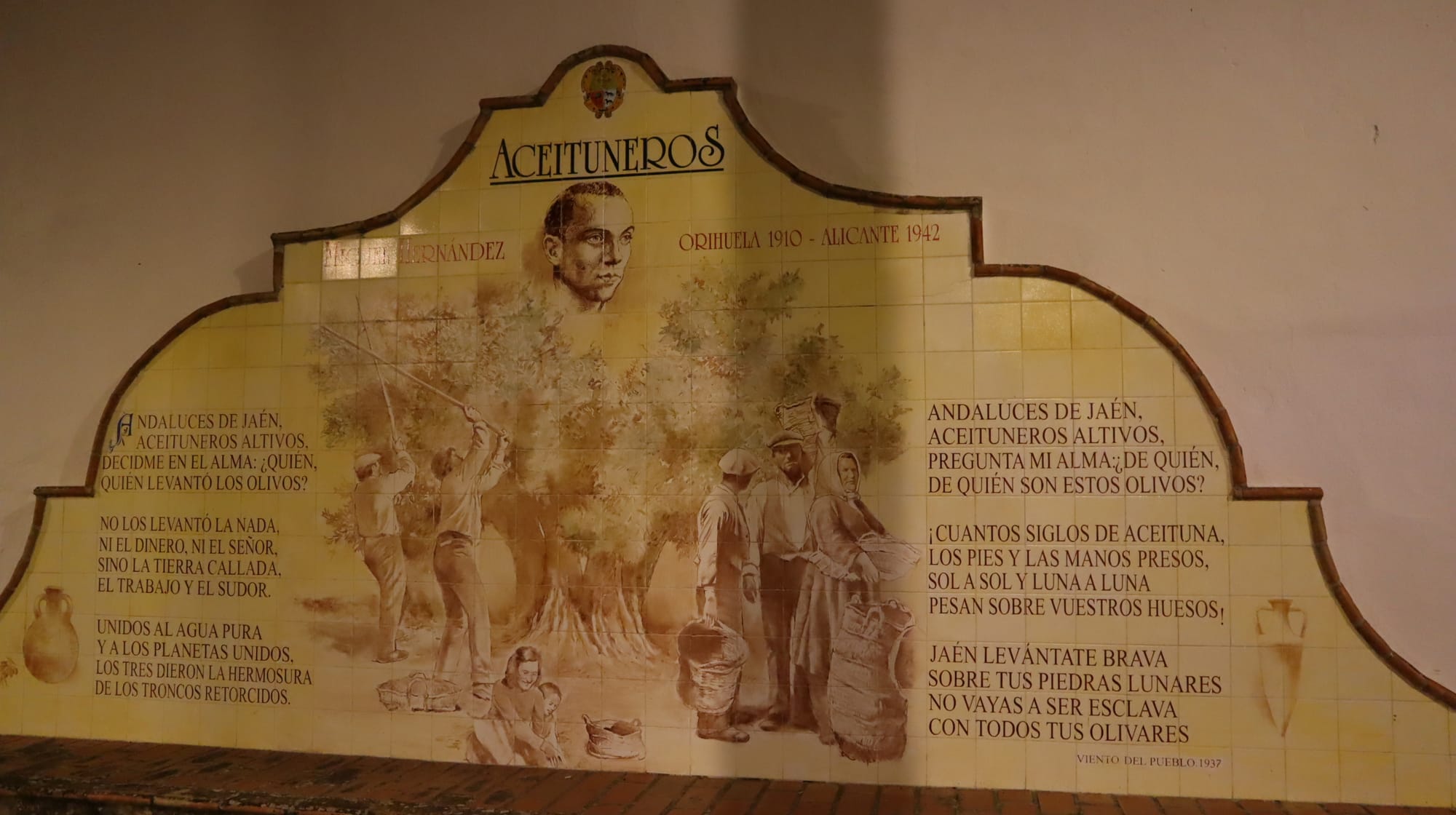

In the heart of the village, a tile mural features the poem Aceituneros — Olive farmers — by Miguel Hernández, one of Spain’s greatest 20th-century poets, who died during the Civil War:

“Andalusians of Jaén, haughty olive growers, I ask you: Whose olive trees are these?”

Just a few meters away, another monument pays tribute to local emigrants. A statue depicts a man with a suitcase and a woman with a baby in her arms, as if these were the only two options for the people of Lopera: tending the olives or leaving.

“We have nothing against renewable energies,” says 35-year-old Manuel Coca, another local olive grower. “But if these solar farms take away what we have, we’re finished. I’ll have no choice but to move to the city and find another job.”

But for some, leaving is not an option. Sitting beside him, Cabezas takes his last sip of coffee. He feels it is too late for him to emigrate and worries for his son. If the olive trees continue to be uprooted, the next generation will be forced to leave.

Like Coca and Cabezas, many people in Lopera believe that it is unfair for the burden of the energy transition to fall on a rural region that is already experiencing a decline in population. Indeed, the Andalusian province of Jaén has seen its population drop from 670,761 in 2010 to fewer than 620,000 in 2024.

However, Mayor Torres Bellido reassures us that the local government is working on a new urban development plan which will give the town council a say in what is installed in the local area, ensuring that the landscape and heritage are respected.

Nevertheless, as Mérida points out, the future of such solar projects is uncertain. “Photovoltaics are booming now, but will they still be in 20 or 30 years? The basic precautionary principle should prevent us from making irreversible changes to this land.”

Top image: An olive tree trunk chopped down nearby Lopera, Andalusia, Spain (Bernardo Álvarez-Villar)

Editor’s Note: This story is part of the series “An Extractive Transition,” which offers a preview of the magazine we have in mind. It was produced as part of the first edition of the Magmatic School of Environmental Journalism.