In this edition of Lapilli+, we highlight an initiative addressing marine litter in western Greece, focusing on pollution from abandoned marine net-pen farms. When fish farming operations go bankrupt and leave their structures at sea, the resulting debris poses risks to wildlife, ecosystems and maritime activities. Such conduct contributes to a pressing environmental issue, which heavily affects the Mediterranean Sea, where litter densities are comparable to those observed in the five major ocean gyres, according to a 2015 study.

Marine litter pollution originates from a variety of sources, both sea-based and land-based, each contributing significantly to the problem. Sea-based sources include fisheries and aquaculture activities, shipping and offshore mining. On the other hand, land-based sources include poor waste management practices, industrial outfalls, untreated municipal sewage discharges, tourism and recreational activities.

Marine litter poses a significant and multifaceted threat. Among the key impacts are the entanglement and ingestion of marine litter by wildlife, which can lead to injury or death. Plastics also contribute to bioaccumulation and biomagnification of toxic substances that are either released from plastic items or adsorbed onto plastic particles (editor's note, they can stick to plastic particles). Furthermore, marine litter can cause direct physical damage, such as the abrasion of coral reefs by fishing gear and the smothering of organisms living on or near the seabed, all of which compromise the health of marine ecosystems. In addition, recent studies highlight that plastics can act as threat multipliers, intensifying the effects of other stressors like climate change and they can introduce invasive species that disrupt ecosystems.

From our correspondence with Thomais Vlachogianni, Environmental Chemist and Ecotoxicologist, Senior Policy & Program Officer at the Mediterranean Information Office for Environment, Culture and Sustainable Development (MIO-ECSDE)

In Menidi, a small coastal village along the Ambracian Gulf in Greece, technical diver Pascal van Erp witnessed a grim scene last October. While volunteering for the second chapter of the “Operation Ghost Farms — Reclaiming Waters” project, the founder of the nonprofit organization Ghost Diving was saddened by the sight of a few dead grey herons floating inside a recently abandoned fish farm structure.

On previous occasions, van Erp came across carcasses of sea mammals or birds trapped in these structures. They knew there is fish inside those cages, he explained, but when they go in to catch it, they can’t get out and die.

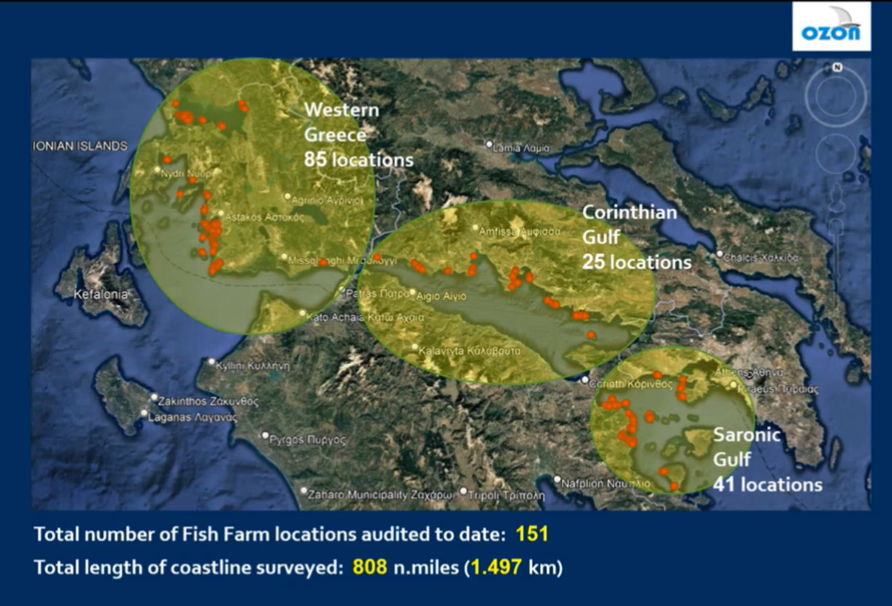

Apart from occasionally killing wildlife, abandoned fish farms mostly pose a threat to boat traffic and the marine environment. Their structures made of plastic, styrofoam, ropes and metal degrade over time becoming marine litter. Sunken nets may suffocate the vegetation and animals on the seafloor (but also host new ones). As plastics and styrofoam deteriorate, these materials can be ingested by marine life, leading to injuries or death, and entering the food chain. According to a couple experts I reached out to for this newsletter, the problems posed by ghost fish farms are potentially and likely relevant in all areas that have a long presence of marine net-pen aquaculture. In Greece, according to a survey conducted by Ozon, a local partner of the Healthy Seas Foundation, the Dutch nonprofit coordinating the “Operation Ghost Farms — Reclaiming Waters” project that Pascal van Erp took part in, 150 coastal sites are potentially polluted by fish farming-related waste.

“It is challenging to determine the full extent of the issue with abandoned fish farms,” wrote Thomais Vlachogianni, senior marine litter researcher at the Mediterranean NGO Federation’s Mediterranean Information Office for Environment, Culture and Sustainable Development, in an email. “As it has not yet been extensively studied or widely reported.”

Healthy Seas leadership first stumbled upon the issue in the summer of 2020 while removing derelict fishing nets from a World War II submarine off the coast of Kefalonia, an island in the Ionian Sea, about 18 miles from mainland Greece. During a short break on nearby Ithaca, locals approached the Dutch foundation team with a tip, recalled Healthy Seas director Veronika Mikos: “If you want to clean up something really big, we've got the fish farm here.”

They were referring to a failed facility that was abandoned at the start of 2010. Over time, storms scattered broken pipes, ropes and other remnants across the coastline. Locals complained that the debris obstructed boat traffic, caused personal injuries and damaged property. They reported the issue to the police, while the island’s mayor raised the matter in the Hellenic Parliament. The Coast Guard issued fines, and a court case addressed unpaid loans, wages and social security contributions owed by the bankrupted company.

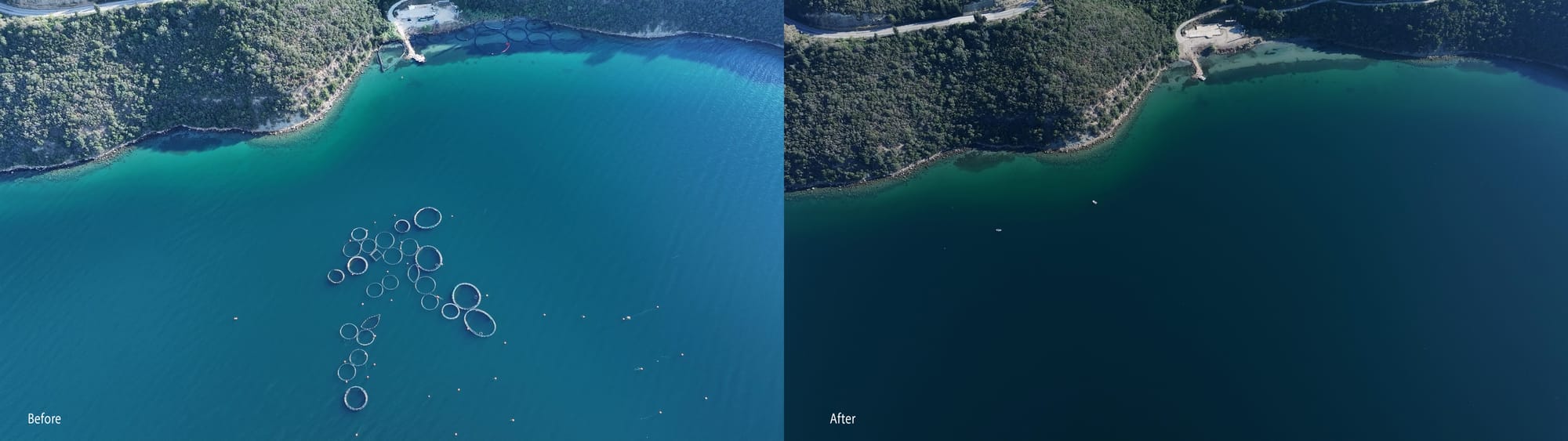

Despite all these efforts, the abandoned fish farm was still there: roughly 22 plastic and styrofoam rings, many of which had broken apart and either washed ashore or lingered underwater with the nets.

“We looked at each other [and thought]: Can we do something to help the local community and protect the environment?” Mikos recalled. So they began mobilizing support, raising awareness and seeking funds to clean up the site.

“When we showed interest in taking action, the regional government issued a permit for us,” Mikos said. The authorities essentially confiscated the area where the fish farm had operated, preventing the bankrupted company from accusing anyone of stealing material. “It was the first time that they did something like this in Greece.”

The cleanup, which was completed over two years, revealed the extent of environmental damage. Pascal van Erp still vividly remembers the impact the sunken structure had on the Posidonia meadows, a vital habitat for Mediterranean marine life. He recalled seeing dead seagrass everywhere.

“That was very sad,” he said.

The organization soon figured that the ghost fish farm in Ithaca was not the only one in the country. “When the press release came out, we started getting calls from other parts of Greece,” Mikos said. “That’s when we realized we had only touched the tip of the iceberg.”

In May, the nonprofit cleaned up another long-abandoned facility near Patras, and, last October, they tackled the recently inactive site in Menidi.

According to Tommaso Petochi, a researcher at the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research’s Unit for Sustainable Development of Aquaculture, the problem stems partly from the structure of the Mediterranean aquaculture industry. Historically, the sector has been dominated by small- and medium-sized enterprises, often lacking large capital and sometimes managerial skills, in a highly competitive field.

“Theoretically in a bankruptcy situation, regardless of the cause, funds set aside for the eventual decommissioning of the fish farm should become available,” Petochi wrote in an email. “But the resources to do so, when they exist, may prove insufficient.”

The sector is also grappling with climate change and increasingly frequent extreme weather and sea events, while access to natural disaster compensation funds remains difficult.

In recent years in Greece — which according to an industry report is the leading producer of seabream and seabass in the European Union — the sector has been facing challenges due to rising production costs, inflation and increased competition from Türkiye.

But overall the aquaculture industry is growing, not just in Greece but across the world, as the Healthy Seas Foundation highlighted in a follow-up email. As more fish farms open without proper controls, support or regulations, they too might encounter a similar destiny and go bankrupt and leave all their facilities and litter behind.

“We are not here to take any sides,” said Veronika Mikos. “We are just here to show that with collaboration, solutions can be found.”

Unlike the broader issue with derelict fishing gear — which, according to Thomais Vlachogianni’s research, can account for 20 to 38 percent of the litter found on coastlines or the seafloor (even though such findings can vary significantly across different areas and depend on many different factors) — owners of abandoned fish farms are not a mystery.

“We are not here to do blaming and shaming,” said Mikos. “Don't misunderstand: We don't intend to become the garbage man of the sector. We do the cleanups to raise awareness about the problem and find the ultimate solutions.”

The idea is that by building public pressure around this topic, those who should take action will be compelled to act. In the meantime, Healthy Seas encourages anyone who encounters or is aware of a ghost fish farm in the Mediterranean region to reach out.

GUIA BAGGI

As an independent journalist, she writes about the environment, as well as the relationship between humans and their surroundings. In recent years, she has been focusing on the impacts of climate change and other environmental crises on the Mediterranean region. Building on this experience, she co-founded Magma.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in February.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. We put a lot of time and love into making Lapilli+, so we think it's fair to ask less than the cost of a coffee for it. Please switch to the Lapilli Premium plan here; it includes a free two-month trial.

Lapilli+ is a monthly newsletter with original content about the Mediterranean and its environment curated by Magma. Here you can read Magma's manifesto.