It was a particularly eventful August, marked by heatwaves, record-breaking fires and powerful storms. In France, the use of air conditioning, which remains relatively uncommon, has become a political issue. In the western Mediterranean, venomous blue dragons have been spotted, while researchers have identified one of the drivers behind marine heatwaves. Meanwhile, on a small island south of Athens, Greece, activists successfully stopped a fish-farming project that threatened to cause significant environmental damage.

All this — and much more — in the latest issue of Lapilli, the newsletter that connects the dots between the month’s stories on the Mediterranean, its environment and climate change. Enjoy!

Mega fires. At the start of August, large wildfires broke out across several Mediterranean countries. In southern France, the Aude region — around Carcassonne — saw the country’s largest fire since 1949, burning more than 16,000 hectares. French Prime Minister François Bayrou said drought and climate change had made the disaster even more devastating (The New York Times).

In Spain, a 16-day heatwave — “the most intense on record”, according the country’s state meteorological agency (AEMET) — fueled wildfires across the country, especially in the northwest. Near Zamora, on the Portuguese border, one of the largest fires raged for weeks. According to the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS), more than 1,570 square kilometers (600 square miles) have burned in Spain since the start of the year — well above the 18-year average (Il Post).

Things were no better in Greece, where several fires affected the western part of the country around Patras, some Ionian islands and Chios in the Aegean Sea. Satellite images revealed that about 100,000 acres were affected by flames in just two days (Kathimerini).

At a European level, 2025 was the worst year on record in terms of the number of hectares burned, around one million (3,800 square miles), an area larger than the island of Cyprus (Euronews). And, according to the World Weather Attribution, drought, high temperatures and strong winds — the weather conditions that caused and fueled the large fires in July in Greece, Turkey and Cyprus — have been made 10 times more likely by human-induced climate change.

Stormy winds. Stormy events soon followed. Off the coast of Menorca, during a regatta, a historic sailing vessel from Monaco suddenly found itself in the middle of a storm with winds over 50 knots and the main mast broke like a breadstick. In Milano Marittima, in Emilia Romagna, more than 300 maritime pines fell due to winds that reached 100 kilometers (62 miles) per hour during a sudden storm. The incident sparked debate on how to manage urban greenery, taking into account that these types of events are becoming more frequent as the Mediterranean region is warming faster than the global average.

The Strait of Messina Bridge gets green-lit. The Italian government has given final approval for the construction of a bridge over the Strait of Messina, allocating €13.5 billion to the project. The decision has reignited a long-standing debate between supporters and opponents of the plan (Reuters, Reuters, NPR, BBC, AP). For background, La Repubblica’s documentary, “The Bridge That Isn't There,” explores both the beauty of the site and the controversy surrounding the project.

Fish-farm expansion blocked in Poros. Finally, the intensive sea farming of sea bass and sea bream along the coasts of the island of Poros won't happen. After 15 years of appeals and resistance from the local population, scientists and fishermen, the plan to create a huge fish farm that would have produced an amount of fish equal to France's production and involved approximately 25 percent of the island's coastline was formally cancelled by the Greek Ministry of the Environment owing to the enormous environmental impact it would have had on the marine ecosystem. In particular, the farm would have had a negative impact on the vast meadows of Posidonia oceanica, a species of marine plant that oxygenates the water and is the basis of the Mediterranean marine ecosystem.

The role of winds in marine heatwaves. A recent study led by the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change (CMCC) has shed light on the factors that trigger marine heatwaves, making them easier to predict. According to the study, the sea warms rapidly when the prevailing winds that disperse the accumulated thermal energy are absent — essentially, when there is almost no wind. This often occurs in connection with what are commonly called African anticyclones, masses of warm air that, once they reach the Mediterranean, interrupt the eastward atmospheric flow and reduce local winds. If these intrusions persist for more than a few days, the seawater begins to warm up.

Over the past 20 years, marine heatwaves have increased in frequency, duration and intensity. The strongest occurred in June 2022, when temperatures 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal were recorded in the Ligurian Sea and the Gulf of Taranto. Marine heatwaves stress ecosystems and can cause the deaths of a number of particularly vulnerable species. Knowing what triggers them and therefore being able to predict them in advance could help prevent or mitigate the damage they can cause.

Venomous sightings. A warmer sea also means a different environment, one that can welcome fish species accustomed to higher temperatures. In previous newsletters we have highlighted the invasion of blue crabs and lionfish. Recently, the Washington Post has reported on the phenomenon, focusing on what is happening in Greece, where the diet has remained mostly unchanged for about 3,500 years. But, with the rise in temperatures, the types of available fish are changing and some see this as an opportunity to introduce new dishes to the country.

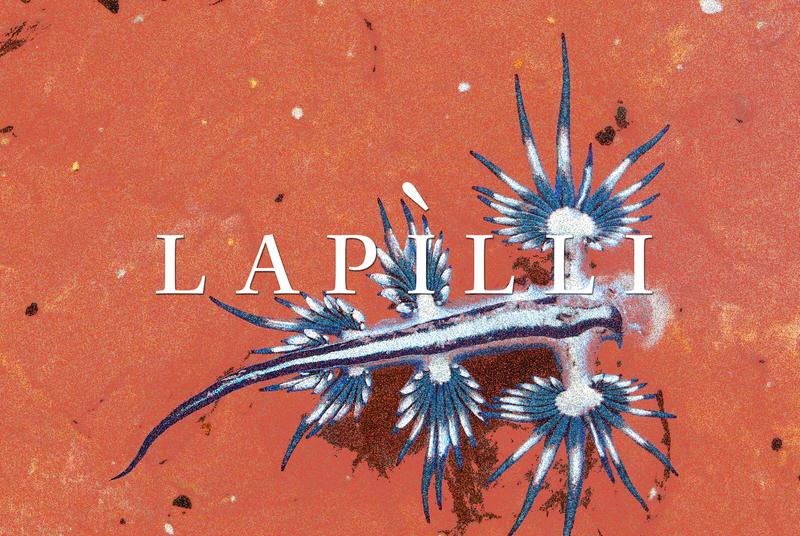

In Spain, where the lionfish is expected to arrive at some point too, they're dealing with another unusual species usually found in tropical waters: the blue sea dragon, a mollusk with a curious dragon-like shape. Earlier this month, two specimens were found on the beach of Guardamar del Segura, south of Alicante. A few weeks later, however, many more arrived, forcing the authorities to close the beaches.

This sea slug, unlike its other relatives, doesn't live on the seabed but floats, drifting with the currents. It feeds on jellyfish, including the most venomous ones like the Portuguese man-of-war, and incorporates their venom into the finger-like appendages on its extremities. An increasingly warm Mediterranean is favoring their spread along with the Portuguese man-of-war (The New York Times).

Air conditioning yes, air conditioning no. Most of the summer and its heatwaves are likely behind us, but the debate remains around air conditioning: yes or no? It is now clear that Mediterranean summers are getting hotter. And this, in addition to impacting tourist flows, is also generating a debate about the use of air conditioning. In many European countries, less than half of homes have air conditioning. In France, the issue became a hot political topic when Marine Le Pen, the far-right leader of the National Rally called for more air conditioning for everyone, while the leader of the Green Party, Marine Tondelier said the answer to extreme heat should be investing in urban greenery and energy-efficient buildings. In France, only 20 to 25 percent of homes have air conditioning, compared to 50 percent in Italy and 40 percent in Spain. But, as summers are becoming increasingly hot, air conditioning is a tool for survival and can literally save lives. According to a 2021 study published in The Lancet, air conditioning helped prevent nearly 200,000 premature heat-related deaths in 2019. The problem is that air conditioning contributes to approximately 3.7 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions. The hope is that AC systems will become more and more efficient and that they will be powered more and more by renewable sources, such as wind and solar, thus reducing their environmental impact no matter how much we come to rely on them in the future (Il Post).

At the same time, there are already numerous tools and techniques for cooling cities and buildings. Some of them are very ancient and have a limited environmental impact. They know something about this in Seville, Spain, one of the hottest cities on the continent — from 2020 to today, Seville has recorded an average of 115 days a year with temperatures above 29 degrees Celsius (84 degrees Fahrenheit). Here, they're rediscovering passive systems for capturing cool air and then releasing it through special grilles introduced by Arabs over 1,000 years ago. They use cold water to cool rooms and roofs, and then hang tarps to create shade on the sunny streets. The ritual of the siesta also has a long, time-tested and very practical reason: During the hottest hours of the day, it's best not to work under the sun. All this is well explained in an article in The New York Times, which explores the various methods, both ancient and modern, that have long been used in Seville to live comfortably even in high temperatures.

Reintroducing horses to prevent fires. We say goodbye with two videos from opposite shores of the Mediterranean. The first takes us to Spain, where a group of conservationists is reintroducing wild horses into the Alto Tajo Natural Park in the province of Guadalajara, with the aim of improving the area’s biodiversity and attracting new residents to one of the most depopulated regions of Spain. Among the many benefits, the horses also help prevent fires by grazing down vegetation (Mongabay).

Changing fisheries. The second brings us to Beirut and shows how fishing in Lebanon has changed in recent years, and how there are fewer and fewer fish — through the words of an elderly fisherman who, despite everything, still heads out to sea at dawn to fish.

GUGLIELMO MATTIOLI

As a multimedia producer, he has contributed to innovative projects using virtual reality, photogrammetry, and live video for The New York Times. In a past life, he was an architect and an urban planner, and many of the stories he produces today are about the built environment. He has worked with publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, and National Geographic. Born and raised in Genoa, Italy, he has been living and working in New York City for more than 10 years.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in October or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma.