In this month’s Lapilli, we focus on “mermaid tears” (those little plastic beads you might have found on the beach last summer), carbon dioxide emissions that the war in Gaza might have generated and the pasta global food-supply chain. Additionally, we have also selected a variety of stories including the potential role of artificial intelligence in tracking illegal fishing activities, the fascinating alliance between plants and fungi, and the adoption of holistic agricultural practices by some Mediterranean wineries to adapt to the changing climate. We hope you’ll enjoy it!

The ubiquity of plastic pellets. Thanks to a grant from Investigative Journalism for the European Union, journalist Marcello Rossi and I investigated the pollution caused by plastic polymers in Europe. Some people dub them “mermaid tears” — probably because when you find them in the sand they look like small crystals — but they are mostly referred to as “pellets” or “nurdles.” Such plastic polymers link natural gas and oil to the plastic objects we use daily. Essentially, every piece of plastic originated from a basic set of polymers.

This raw material, which is still relatively inexpensive and produced by a handful of multinational corporations, disperses into the environment in quantities estimated at roughly 165,000 metric tons annually in the European Union alone. A recent incident off the coast of Galicia highlighted the devastating environmental impact when the loss of containers during maritime transport caused millions of plastic pellets to scatter at sea (Reuters).

Polymers — the largest of the microplastics — measure roughly 5 millimeters (0.2 inches) in diameter, at least initially. Over time, they break down into even smaller particles, are eventually absorbed by the marine environment and enter the human food chain. The European Commission is now aiming to regulate the production and transportation of these “pellets.”

In our investigation, we ventured into some of the major plastic polymers production hubs, such as Tarragona in Catalonia and Brindisi in Apulia, to understand why this silent contamination is not being adequately contained. The findings can be explored on EUObserver in English, on Climatica in Spanish, and will be available also in Italian soon.

The environmental impact of the war on Gaza. Drawing from a recent study released on the Social Science Research Network, a Guardian article delves into the carbon dioxide emissions caused by the conflict in Gaza. In the first 60 days of the war, it is estimated that 281,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide were released into the atmosphere, which is the equivalent of burning 150,000 metric tons of coal. To put it in perspective, this surpasses the annual carbon dioxide emissions of smaller countries like Belize or the Central African Republic. According to the study, and as reported by The Guardian, approximately half of these emissions primarily stem from the transport of weapons and bombs from the United States to Israel.

However, this calculation does not account for the environmental impact of the production of the weaponry used, nor does it consider the potential costs for the reconstruction of the more than 100,000 destroyed and damaged buildings. In this case, the calculation could be five to eight times higher than currently estimated. These figures are not meant to detract from the human tragedy of more than 25,000 casualties but rather to prompt reflection and indignation over a military action that has surpassed any justifiable rationale.

The long journey from wheat to pasta. Slow News has released the latest episode of “Mani in Pasta” (“Fingers in Every Pie”). In this series of reports, resulting from a year-long investigation, journalist Sara Manisera retraces the entire pasta supply chain — now a globalized food — from Mesopotamia to the Wheat Library near Salerno, passing through the hills of Burgundy, in France, and those of Basilicata, in southern Italy, which is home to one of Europe's largest wheat mills. She found how many cereal varieties we consume, who controls the supply chain and which oligopolies oversee the trade of cereal, which is a crucial foundation of our diet. All articles are available in Italian and English here.

Mycorrhiza: The alliance between the plants and fungi. The story of an ancient relationship, that between plants and fungi, unfolds through stunning photographs of an alpine landscape. In this Radar Magazine story, journalist Anna Violato and photographer Elisabetta Zavoli delve into the symbiosis between two kingdoms that began 600 million years ago.

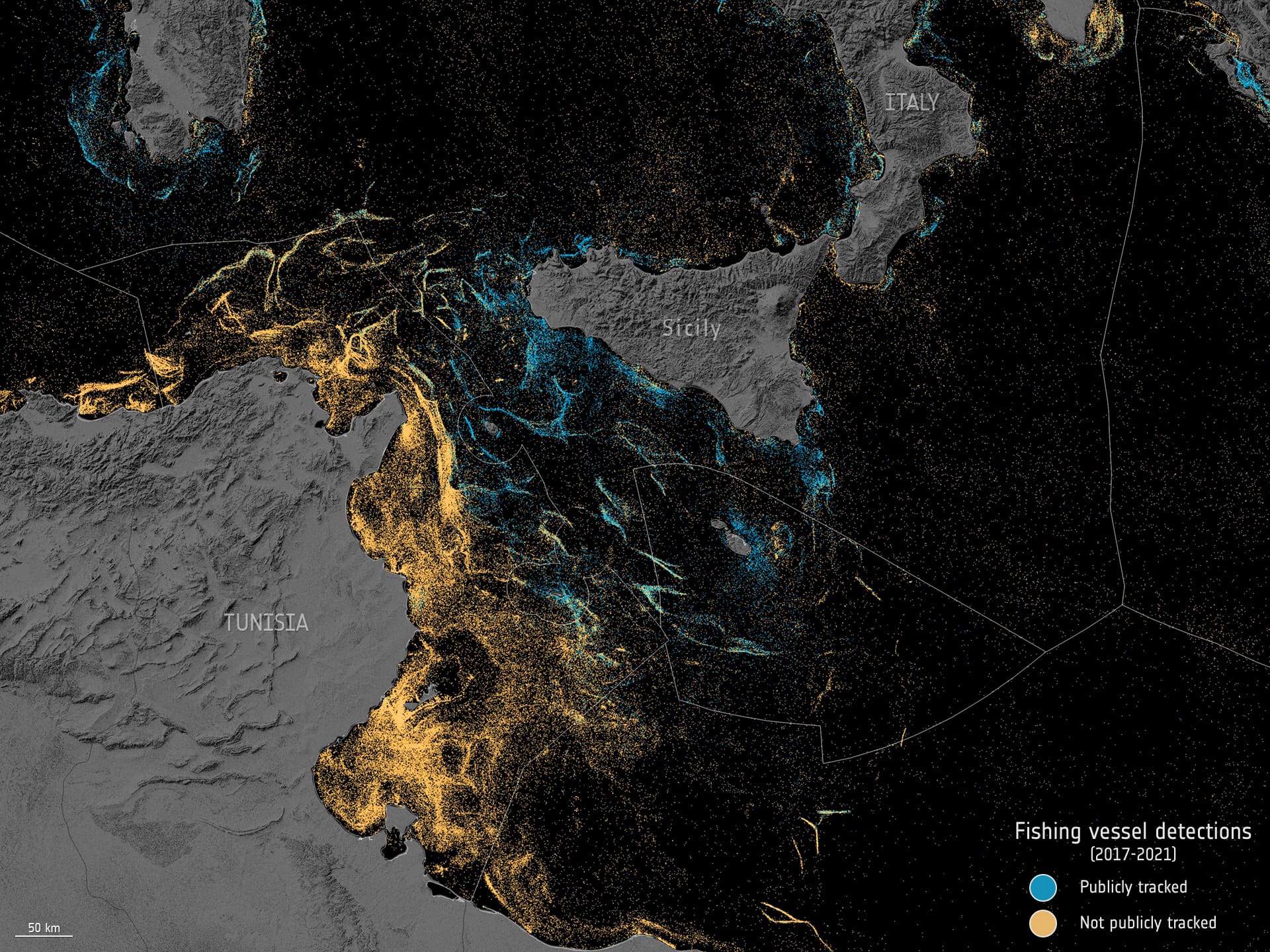

May artificial intelligence help counter illegal fishing? With the assistance of artificial intelligence, a study published in Nature reveals an estimate of industrial fishing vessels worldwide that far exceeds the official data available. According to a complex calculation based on a series of cross-referenced data, about 75 percent of industrial fishing vessels operate without being tracked (Smithsonian Magazine). Vessels engaging with industrial fishing in areas like the Mediterranean are required to have satellite systems, such as Automatic Identification System (AIS) — although small vessels engaged in artisanal fishing are exempt. It was already known that these obligations were being ignored, but the study visually illustrates the magnitude of fishing activities taking place without tracking.

Another study has focused on the environmental impact of trawling in terms of carbon dioxide emissions. As a significant amount of carbon is indeed stored in the seafloor, dragging the seabed, besides harming marine flora and fauna, releases a previously overlooked quantity of carbon dioxide (New Scientist). The combined results of these two recent studies could expedite the implementation of legislative measures needed to address illegal fishing and monitor trawling practices.

Adapting viticulture. As official data show, 2023 was the hottest year ever recorded on the planet. A lingering drought in the Western Mediterranean persists, pushing Catalonia close to an alert threshold with Barcelona's water reservoirs at 16 percent in the heart of winter. In Morocco, the government has opted to close hammams and car washes for three days a week to tackle a drought that has persisted since 2019. Against this backdrop, some Mediterranean agricultural wineries, from the Catalan Pyrenees to Montalcino in Tuscany, are transitioning to a more biodynamic and environmentally integrated farming approach to cope with the challenges posed by the evolving climate conditions.

Melting glaciers. An Arte documentary focuses on the impacts of glacier melting on drinking water. At this link instead you can watch a time-lapse of the Fellaria Glacier in Northern Italy as it melts. It was shared a few months ago by the Lombardy Glaciological Service.

DAVIDE MANCINI

As a freelance journalist, he writes, photographs and films the changes that are affecting the Mediterranean region, with a focus on the environment. He has published several investigations with international media on issues such as forest fires, illegal fishing and sea pollution. Here is a link to his published work.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in March or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma. Here you can read Magma's manifesto.