In this issue of Lapilli, we begin with good news: The overexploitation of fish stocks in the Mediterranean has declined significantly over the past decade, according to a recent report from the General Fisheries Commission of the Mediterranean (GFCM), a regional fisheries management organization under the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Aquaculture has also rapidly grown in the region, helping boost the biomass of several species.

Meanwhile, the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change took place in Belém, Brazil, was marked by logistical hurdles and political tensions. The summit closed with the announcement that the next COP will be held in Türkiye, indubitably placing the Mediterranean at the center of climate discussions.

November, however, is also the season of heavy rains, and when that precipitation falls in places where war has displaced millions and destroyed essential infrastructure, suffering only deepens — which is happening in Gaza.

We then turn our attention to the land, highlighting a story in rural Morocco that goes behind the scenes of the argan oil industry, where the women’s cooperatives that built the sector are now facing increasing pressure. We also feature Syrian farmers, who after returning home after years of conflict, are recovering and planting traditional, local seeds once again.

And finally, a piece of news that means a lot to us at Magma and hopefully to you as well: We have printed the first issue of Magma Magazine. Holding it in our hands was a special moment. The copies pre-ordered during our crowdfunding campaign have already shipped and the magazine will also be available in select bookstores in Italy and Spain, including Libreria del mare (Palermo), Paperback Exchange (Florence), Libreria modo infoshop (Bologna), and soon at Espacio Late (Madrid), where there will also be an event scheduled in January (more in the next edition of Lapilli).

As always, we hope you’ll enjoy the read!

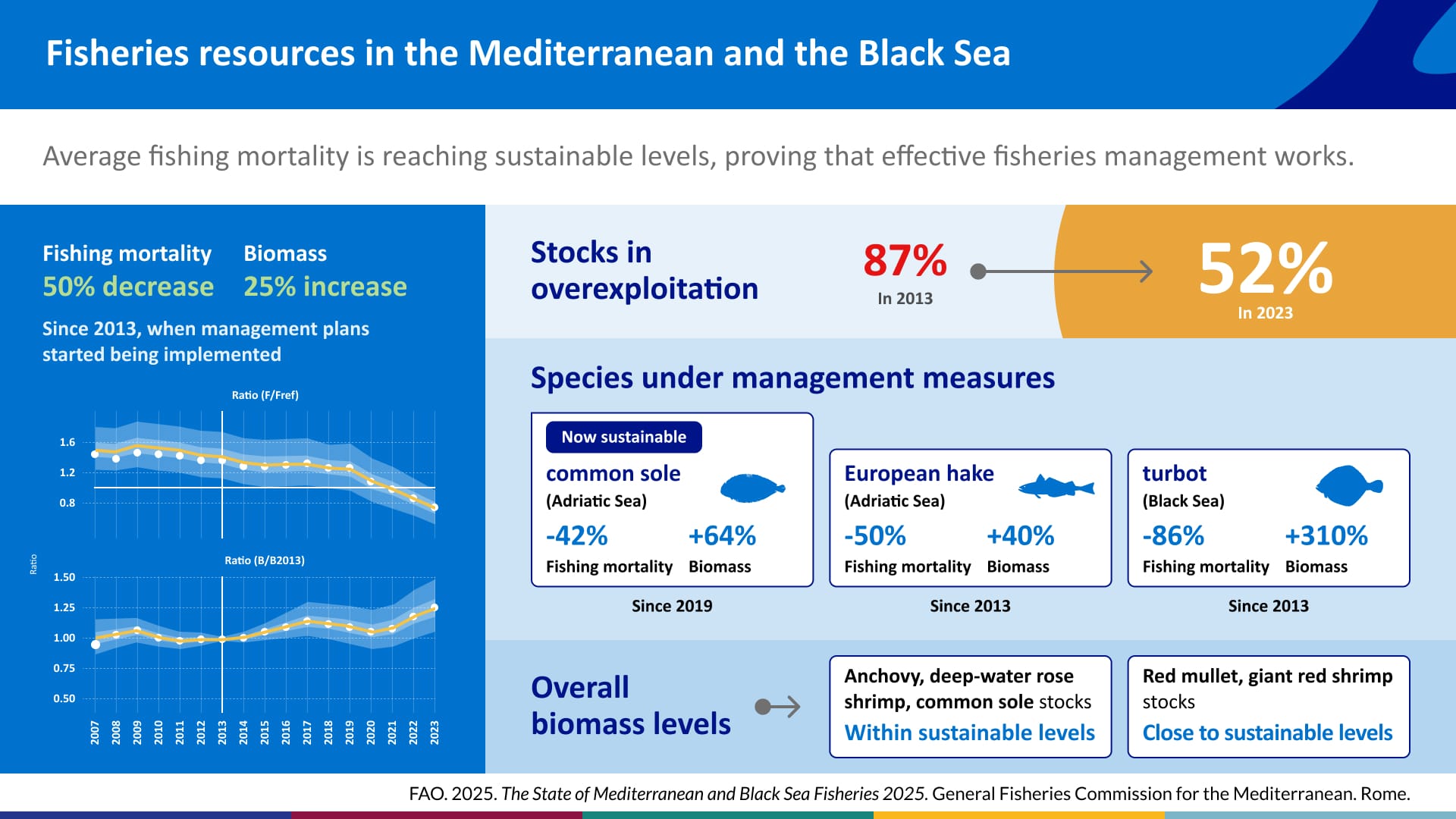

Some fish stocks recover, while farmed fish grow. A few days ago, the GFCM released the latest version of its State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2025. The overall headline is a positive one: Overexploitation of fish stocks has fallen by 50 percent over the past decade. Progress is evident across several key commercial species. Red mullet and giant red shrimp show marked reductions in fishing mortality and species under dedicated management plans are recovering at above-average rates. In the Adriatic, the amount of common sole has risen by 64 percent since 2019; in the Black Sea, turbot has seen an 86 percent drop in fishing mortality and a 310 percent increase in biomass since 2013.

Sardines, however, remain in trouble. After years of heavy pressure, their biomass continues to decline. European hake — showing strong variation between subregions — displays only modest signs of recovery, despite a 38 percent decrease in fishing mortality since 2015.

While fishing pressure eases, the share of fish coming from marine and freshwater aquaculture keeps growing. The report offers the first detailed look at this rapidly expanding sector. Including freshwater production, aquaculture generates $9.3 billion (7.9 billion euros) and produces nearly 3 million metric tons of aquatic food. In 2023 alone, farms produced 940,000 metric tons — more than 45 percent of the region’s total supply.

Marine aquaculture production is concentrated in a few species: 11 species account for 99 percent of total output. Gilthead seabream (34.5 percent) and European seabass (29.7 percent) are the top two farmed species. Ninety-nine-point-five percent of all farmed aquatic food in the region is produced by eight countries, including Türkiye (400,000 metric tons), Egypt (147,000) and Greece (139,000).

The report notes that, although meaningful progress has been made in reducing overexploitation, much more is needed to ensure sustainable aquaculture management — particularly as the sector is set to keep expanding in the years ahead (The Fish Site; Middle East Monitor).

The COP returns to the Med. The COP30 has just wrapped in Belém, Brazil, and many consider it one of the least effective summits yet. The goal of keeping global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) — set in Paris a decade ago — now feels increasingly distant.

No substantial progress emerged on the ecological transition, greenhouse gas reductions or deforestation. And while the COP in Belém did, at least, bring attention to the Amazon, given its setting, we hope that the next COP — to be held in Türkiye — will place the Mediterranean, one of the fastest-warming regions on the planet, high in the agenda.

If you’d like to understand what actually happened in Belém, beyond the logistical issues, we recommend the BBC’s classic five-point summary and a longer article on Grist.

Heavy rains in Gaza. In war-torn Gaza, winter rains become yet another ordeal for displaced families living in tents. The rain, mixed with rubble and the absence of drainage infrastructure, turns the ground into a literal quagmire.

Under the ceasefire terms, Israel is required to allow the daily entry of hundreds of aid trucks, including materials needed for sheltering from the rain. But humanitarian agencies say assistance remains insufficient and that basic tools to drain water, manage waste and reinforce structures are still missing.

Many displaced people describe mounting difficulties: clothes and blankets that cannot dry, firewood that has become too expensive, food meant to be cooked over open fires rendered unusable by the rain. Families live in fear of the next storm, as conditions in the tent camps continue to deteriorate (The New York Times).

Who profits from argan oil? Argan oil — one of the most coveted ingredients in the global cosmetics industry — is extracted from the seeds of Argania spinosa, a tree that grows almost exclusively in Morocco. Traditionally produced by local women through long, labor-intensive manual work, the oil has seen international demand surge in recent decades, prompting the creation of numerous women’s cooperatives in Morocco, which are often presented as models of empowerment and development.

Over time, however, many of these cooperatives have been absorbed — or sidelined — by supply chains dominated by intermediaries and multinational companies, which buy raw oil at extremely low prices before processing and reselling it at far higher margins. Years of drought have made the situation even more difficult, shrinking argan forests by nearly 50 percent.

Today, most of the economic value no longer reaches the women who do the work. Many earn very little, have limited influence over decisions and are often included mainly as an “ethical showcase” in marketing aimed at global consumers (The Ecologist; Internazionale).

Syrian seed rebirth. In the small Syrian village of al-Dheibeh, south of Aleppo, a group of farmers gathered to share and exchange traditional seeds, known as “baladi” — open-pollinated varieties native to the region. Unlike industrial hybrid seeds, engineered to produce abundantly once and then die — leaving farmers dependent on seed companies — “baladi” seeds are living lineages, replanted and reselected season after season.

During the Syrian civil war, which began in 2011, many people fled their homes and large areas of farmland were damaged. Some farmers, however, carried these traditional seeds with them, protecting them like family heirlooms wherever they went, including across the border to Lebanon. It was there, in 2016, that a non-governmental organization called Buzuruna Juzuruna (“Our Seeds Are Our Roots”) was founded to safeguard these varieties while Syria was in turmoil. Farmers, refugees and volunteers worked together to preserve hundreds of local species — vegetables, herbs, grains, medicinal plants and flowers — so they would not disappear. Now that some areas of Syria are safer, the seeds are being brought back and planted once again.

Traditional seeds, unlike industrial ones, thrive in the environments in which they evolved, keep soils healthier, preserve biodiversity and help communities become more self-reliant. By putting them back in the ground, farmers are trying to restore both their landscapes and their sense of belonging after years of war (New Lines Magazine).

One woman’s fight to save Lebanon’s olive trees. To continue on the theme of roots, attachment to one’s land and war, we suggest a short documentary set in Lebanon, where phosphorus bombings have burned — among other things — an 81-year-old woman’s olive trees. In confronting this loss, she has demonstrated that they represent far more than a simple cultivated crop (Al Jazeera).

GUGLIELMO MATTIOLI

As a multimedia producer, he has contributed to innovative projects using virtual reality, photogrammetry and live video for The New York Times. In a past life, he was an architect and an urban planner, and many of the stories he produces today are about the built environment. He has worked with publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian and National Geographic. Born and raised in Genoa, Italy, he has been living and working in New York City for more than 10 years.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in January or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma.