This month’s Lapilli is brimming with stories from across the Mediterranean. It opens with the anniversary of the Valencia flood, moves to the protests in Tunisia against a phosphate-processing plant polluting the air and sea, and reaches the Adriatic coast, where illegal date mussel fishing continues despite longstanding bans.

We then head to Greece where people displaced by the 2023 floods are sharing space in migrant centers while awaiting permanent housing — a tangible example of how climate issues intersect with social and political ones.

We also feature a transnational investigation that visualizes land consumption in Europe (poetically titled “Green to Grey”), the proposed legal personhood of Lake Garda and the Caretta caretta turtles nesting on Italian beaches in record numbers.

As always, there’s much more. Enjoy!

Recounting the Valencia flood. A year after the flood that struck Valencia on October 29, 2024, several articles have been published recounting what happened, the controversies that followed and the prospects for the future.

The disaster was triggered by a DANA — also known as a “cold drop” — an isolated high-altitude depression typical of the western Mediterranean. Such storm systems can generate intense, stationary thunderstorms that release large amounts of rain over a localized area.

When a phenomenon of this kind hits a densely populated region already prone to flooding owing to its geography — which is the case in Valencia — the risks become extremely high. Combined with delays in the state-run warning systems, last year’s flood resulted in more than 200 fatalities, over half of them aged 70 and above (Phys.org).

And the controversy over how local authorities handled the emergency has yet to subside (BBC). A year later, both early-warning systems and land-use planning measures have been revised and reinforced. However, intense phenomena, like last October’s DANA, are expected to become more frequent as a result of climate change, and much remains to be done to prevent similar events from causing hundreds of deaths and billions of euros in damage.

We marked the anniversary of the Valencia flood with a photo-essay by Carlos Gonzalo Gil recently published on Lapilli+, which document the environmental damage that followed the disaster. The environment is often overlooked in these instances, overshadowed by the rightful focus on the victims and the destruction of homes and essential infrastructure.

Protests in Tunisia over phosphate pollution. In the Tunisian city of Gabès, thousands of residents marched demanding the closure of the Tunisian Chemical Group’s phosphate-processing plant, over pollution concerns and a rise in respiratory diseases. “Gabès has turned into a city of death, people are struggling to breathe, many residents suffer from cancer or bone fragility due to the severe pollution,” protester Khaireddine Dbaya told Reuters.

Tons of industrial waste are discharged daily into the sea off the city, devastating marine life, according to environmental groups, and crippling fishing activities. Despite promises made in 2017 to dismantle the plant and build new, safer facilities, it appears that no progress has been made. Tunisian President Kais Saied has called the situation an “environmental assassination” and ordered urgent action. Yet, at the same time, the government aims to quintuple phosphate production by 2030, further heightening tensions between economic development and the protection of public health (Reuters).

Corporations banking on 'made in Italy' tropical fruit. The Swiss-American multinational Chiquita recently announced it will launch the first “made in Italy” banana plantation in Sicily. The project will begin this fall with the planting of 20,000 banana trees, which are expected to begin fruiting as early as 2026. The initiative is based on the growing assumption that the Mediterranean basin is becoming increasingly tropical, making the cultivation of exotic fruits more and more viable. This also marks a symbolic turning point in how agriculture in the region is shifting due to climate change (Il Sole 24 Ore).

The trend is also evident in avocado cultivation, which has become a multi-million-dollar business in Italy — particularly in Sicily — attracting both entrepreneurs and investment funds and transforming the region’s agriculture. Domestic demand is rising rapidly. Per capita consumption has grown from 100 to 800 grams per year over the past decade, and profit margins are high: One hectare of avocados can yield more than twice that of lemons.

As a result, many citrus groves and vegetable gardens are being converted, with land values soaring from around €80,000 ($85,600) to €180,000 ($192,600) per hectare after conversion. Companies have embraced an agritech startup model, raising millions of dollars in funding and investing in advanced irrigation and monitoring technologies. The avocado has become a symbol of the new era of investment-driven agriculture in Italy (Il Post).

When the climate and migration crises overlap. In Greece, the consequences of the flood that hit Thessaly in 2023 are intertwined with the ongoing migration crisis. The September 2023 floods devastated the town of Farkadona, in the heart of the Hellenic peninsula, forcing hundreds of residents to abandon their homes and relocate to reception centers originally intended for foreign migrants and asylum seekers — effectively creating a class of migrants within their own country.

A long-term investigation by Greek nonprofit journalism outlet Solomon titled “Migrants in their Own Land: Climate Displacement at Europe’s External Borders” examines how climate change in Greece is generating new forms of internal migration that overlap with the management of external migration flows, creating social tensions between internal and external migrants who are forced to live together under difficult conditions.

Between 2008 and 2023, Greece recorded more than 213,000 internal displacements caused by extreme weather events, such as floods, fires and storms — the highest figure among European Union member states, according to data from the European Environment Agency. This trend is steadily increasing. Its consequences extend far beyond material damage, encompassing rural depopulation, a loss of social cohesion and the economic weakening of local communities. Greece is also one of Europe’s frontier countries and a key landing point for migrants seeking entry into the European Union.

Finally, the investigation highlights the ineffectiveness of government policies on prevention and adaptation, stressing how a culture of emergency response continues to prevail over long-term planning (Solomon).

Heat affects people unequally. We’d like to highlight an important report analyzing how extreme heat, now increasingly frequent, affects people’s lives unequally — comparing the peripheral and central neighborhoods of Paris and Barcelona.

In the poorer districts of Barcelona (Nou Barris) and Paris (Aubervilliers), residents live in poorly insulated homes, with little greenery and limited access to air conditioning. Sensors installed in these homes recorded indoor temperatures above 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit) with severe health consequences — especially for the elderly, children and vulnerable individuals.

By contrast, in the central and more affluent areas of both cities, homes are better insulated, equipped with efficient air conditioning and surrounded by green spaces and tree-lined streets that help moderate temperatures. Residents also have greater financial resources to pay for energy, install cooling systems or renovate their homes. These areas further benefit from stronger public policies, supported by larger municipal budgets and improved infrastructure.

Paris has established more than 1,400 “cool islands” — including museums, churches, parks and air-conditioned centers — while Aubervilliers doesn’t even have mist stations or shade spots. As one local official admitted, “We don’t have the same resources as Paris. It’s a different reality.”

The same pattern exists in Barcelona, where the new “Heat Plan 2025–2035” envisions major investments in the shading public spaces and creation of climate shelters. Yet, working-class areas, such as Nou Barris, continue to lag behind.

In short, climate change amplifies existing inequalities: The wealthy can buy comfort and safety, while the poor face unbearable temperatures and increasingly unlivable urban environments.

Across Europe, heatwaves intensified by climate change cause more than 40,000 deaths each year. Public measures — such as heat-reduction plans and air-conditioned shelters — remain insufficient in poorer neighborhoods, where investment in building insulation, electric subsidies and green infrastructure is still lacking (Unbias The News).

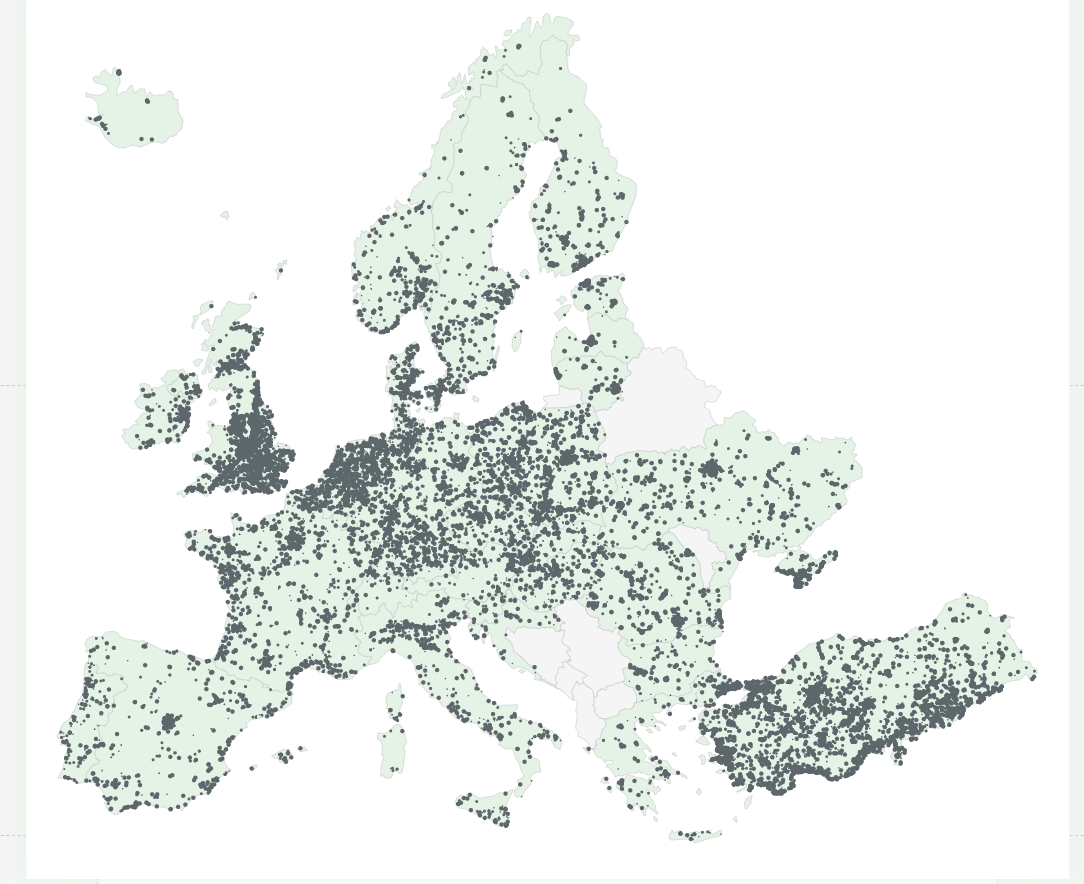

From green to gray. The investigation titled “Green to Grey,” produced by 41 journalists and scientists from 11 European countries, powerfully and visually documents how Europe is rapidly losing its natural and agricultural land. Between 2018 and 2023, the continent lost approximately 9,000 square kilometers (3,475 square miles) of nature and arable land — an area roughly the size of Cyprus — with an average of 30 square kilometers (11.6 square miles) disappearing every week. Each year, roughly 900 square kilometers (347 square miles) of natural areas and 600 square kilometers (232 square miles) of farmland vanish, mainly due to new construction, infrastructure expansion and tourism development. These losses, often small in scale but cumulative in effect, are occurring up to one and a half times faster than previously estimated.

The investigation reveals that 70 percent of new construction takes place within already urbanized zones — including parks, green spaces and even coastal or protected areas — further exacerbating environmental degradation. Türkiye has suffered the most extensive losses: Between 2018 and 2023, 1,860 square kilometers (718 square miles) of natural and agricultural land were destroyed, including the Çaltılıdere wetland, which was converted into a large shipyard for luxury yachts. The project has sparked local protests, as the area — once home to flamingos and fish — was stripped of its protected status to allow for development.

In Portugal, a new 300-hectare (740-acre) golf resort, the Costa Terra Ocean and Golf Club, has been built on the Galé dunes, within a Natura 2000 protected area. Despite environmental risks — such as the daily consumption of over 800,000 liters (211,000 gallons) of water and the heavy use of fertilizers — the project was approved by Portuguese authorities for socioeconomic reasons. Residents have denounced the privatization of public land and the devastating impact on coastal biodiversity.

In Italy, the shores of Lake Garda are under threat from tourism-driven development, while in Greece, the Vermio Mountains are being transformed into wind farms, with new roads cutting through once-pristine landscapes. According to scientists, the combination of tourism and infrastructure expansion is destroying some of the last remaining ecosystems in southern Europe.

The investigation concludes that, despite EU commitments to achieve the 2050 goal of “no net land take” — when the area of land converted to artificial surfaces equals the area restored to natural or semi-natural conditions — soil loss continues. Without binding targets, new laws, such as the Nature Restoration Regulation that was adopted in 2024, are put into jeopardy and at risk of becoming useless. “We cannot live in a concrete desert,” ecologist Peter Verburg warned in the Green to Grey investigation. “We need nature to survive climate change.” The full investigation, including photos, graphics, and videos, can be found online.

The increasingly urbanized Lake Garda. One chapter of the Green to Grey investigation examines Lake Garda (to which our very own Davide Mancini has dedicated the cover image of this issue of Lapilli), where natural soils are increasingly at risk due to the relentless growth in tourism. Satellite imagery reveals that construction is steadily replacing natural areas, leading to a decline in habitats for local flora and fauna. Only a small portion of Lake Garda’s shoreline is protected — primarily along the Veneto side and within the Alto Garda Bresciano Park.

Tourism on the lake, which began in the 19th century with the opening of the first hotel in Gardone Riviera, has now experienced exponential growth: 25 million overnight stays were recorded in 2023, a 30 percent increase over the past decade. Official statistics do not include short-term rentals, which further inflate tourism numbers.

Meanwhile, the resident population is growing slowly, and seasonal residential complexes — empty for much of the year — continue to multiply. Mass tourism and ongoing construction have transformed the area, reducing the quality of life for locals. Even initiatives considered “sustainable,” such as the suspended cycle path along Lake Garda, have drawn criticism for their environmental impact and increased risk of landslides along the cliffs. Experts warn that such projects, rather than reducing traffic, attract even more visitors, intensifying pressure on an already fragile ecosystem. The transformation of the landscape — made more “convenient” and artificial to serve tourism — has led to a loss of its natural authenticity.

Today, Lake Garda is an emblem of overtourism being not only a social and economic challenge but an ecological one too (Il Bo Live). Some propose granting Lake Garda legal personhood — a status similar to that of the Mar Menor in Spain, which we’ve discussed in previous Lapilli newsletters. This recognition would allow the lake’s rights to be considered in administrative decisions and, ultimately, make it possible to take legal action against anyone who compromises its integrity (Il Bo Live).

Bosnia’s craving for date mussels. Off the coast of Neum, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s only Adriatic port, local divers continue to illegally extract date mussels, shattering rocks on the seabed — a practice banned throughout the European Union owing to its severe environmental damage. The mollusk is then sold at a high price to local restaurants, where it features prominently on menus and is also served to tourists. In just a few hours of diving, a single diver can collect up to ten kilograms (22 pounds) of date mussels, which are resold to restaurateurs for around €25 ($27) per kilo and served to customers for more than double that price.

Demand is driven by wealthy clients, not only along the coast but also inland, including in Sarajevo, and even by Croatians who cross the border to enjoy a delicacy that is prohibited in their own country.

The extraction of these mollusks destroys coastal rock formations, erasing vital habitats for fish, octopuses, crustaceans and algae, with irreversible consequences for marine biodiversity. Date mussels take up to thirty years to reach edible size, and the loss of their rocky substrate compromises the ecosystem for decades.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, fishing is banned only in the Herzegovina–Neretva Canton, where Neum is located, creating a regulatory loophole that renders enforcement ineffective across the rest of the country. Local authorities acknowledge the lack of inspections, while many restaurateurs admit they will continue serving date mussels until a nationwide ban is enacted.

In contrast, Croatia enforces strict laws: The harvest and sale of date mussels is prohibited nationwide, inspections are frequent and fines exceed €1,000 ($1,070). Authorities even equate the smuggling of date mussels with drug trafficking, underscoring the seriousness of the offense (Balkan Insight).

More and more turtles are nesting in Italy. Over the past year, 700 Caretta caretta nests have been recorded in Italy. Last year, 601 nests were recorded, while in 2023, there were 443. On the one hand, this uptick can be attributed to better protection and safeguarding of beaches. On the other hand, with the increase in temperatures from climate change, the coasts of the western Mediterranean have become better suited for the egg-laying of this species (Il Post). Former Magma fellow Vittoria Torsello recently published a story on this very topic, focusing on the beaches of Salento — among those with the highest number of nests, yet also the most developed and crowded. The story highlights the difficult coexistence between tourism and turtle conservation in that area as well as the delicate balance between natural habitats and human activities (Lifegate).

A sea surrounded by mountains. Extreme floods with return periods of more than 500 years — like the one that struck Emilia-Romagna in 2023 — could become increasingly frequent in a Mediterranean basin that is warming up. According to the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change, the region’s geography plays a crucial role in this growing vulnerability. The Mediterranean is a closed basin, encircled by mountain ranges — the Alps, Apennines, Pyrenees, Balkans and Atlas — which act as natural barriers, trapping moist air from the sea.

This phenomenon, known as the “cul-de-sac effect,” causes rain clouds to stall over the same areas for days, transforming valleys and plains into vast flood zones. This is precisely what happened in Emilia-Romagna in 2023, when the equivalent of six months’ rainfall fell in just 36 hours, causing 17 deaths and €8.5 billion ($9.1 billion) in damage.

Compounding the problem is global warming, which makes the atmosphere warmer and capable of retaining about 7 percent more moisture for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degree Fahrenheit) increase in temperature. Between 1980 and 2022, floods in Europe caused 5,582 deaths, and in 2023 alone, they accounted for 81 percent of all economic losses linked to climate-related disasters. The development of forecasting and preparedness tools to address these increasingly frequent events has therefore become an urgent priority.

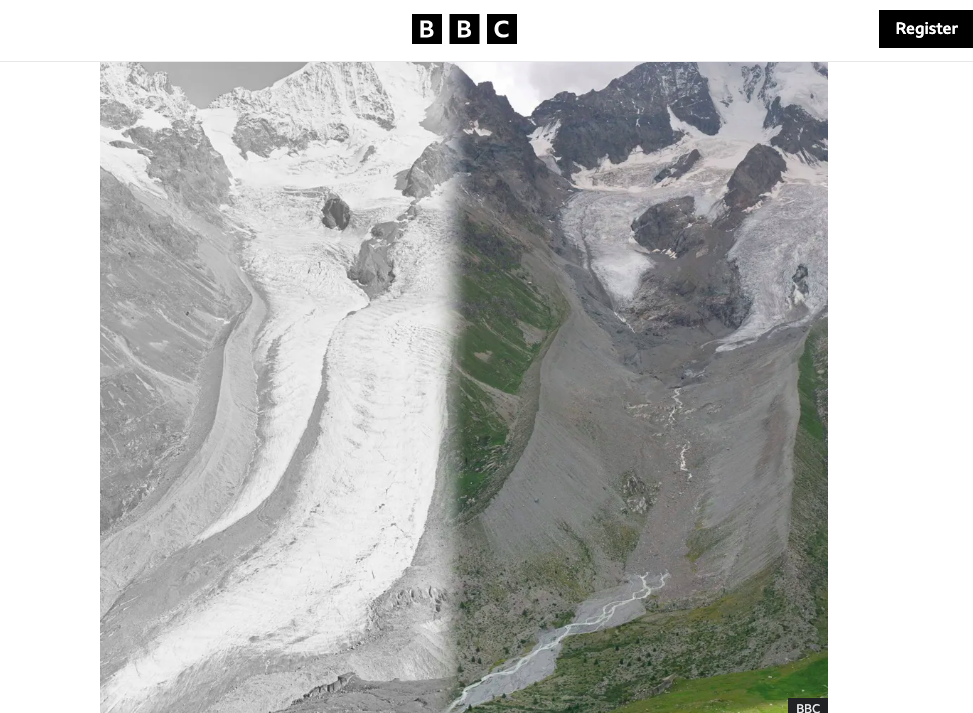

A melting future. We’ll leave you with a feature that, through striking comparative images, vividly illustrates the melting of Alpine glaciers, particularly in Switzerland. Global warming, driven by human carbon dioxide emissions, is identified as the main cause, with melting rates now far exceeding normal natural variability.

Even if global temperatures were to stabilize today, much of the remaining ice would continue to melt due to the delayed effects of climate change. However, scientists note that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) could still save around half of the world’s mountain glaciers — a stark reminder that decisive action can still make a difference (BBC).

GUGLIELMO MATTIOLI

As a multimedia producer, he has contributed to innovative projects using virtual reality, photogrammetry, and live video for The New York Times. In a past life, he was an architect and an urban planner, and many of the stories he produces today are about the built environment. He has worked with publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, and National Geographic. Born and raised in Genoa, Italy, he has been living and working in New York City for more than 10 years.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in December or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma.