In this issue of Lapilli, we take stock of the past summer. From there, we travel to Syria, where drought is compounding fragile post-civil war conditions, and Morocco, where desalination plants seem only to be a temporary relief from the ongoing seven-year drought and not a lasting solution. We then head to Egypt with some good news on migratory bird protection, before turning to an interactive map that vividly illustrates how emissions from ports, factories and power plants spread across the atmosphere. And, as always, much more. Happy reading!

Drought in an already strained Syria. Syria is facing its worst drought in nearly forty years, and in an already fragile environment following years of civil war. Rainfall has dropped by 70 percent and wheat production may fall to just one million tons — down from 3.5 to 4.5 million tons before the conflict. This sharp decline threatens food security: More than 14 million Syrians are eating less than they need and more than 9 million are experiencing acute food insecurity.

Harvest failures have pushed bread prices up ninefold in a single year, hitting the poorest families hardest. The drought’s effects are only compounded by the war’s damage, including destroyed irrigation systems, minefields and shattered infrastructure.

The interim government, led by President Ahmed al-Sharaa, is exploring solar-powered drip irrigation projects, though these require time and investment. In the meantime, organizations such as the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Food Program are providing food aid and financial support to smallholder farmers. In the longer term, however, Syria will need to rebuild a resilient agricultural sector — one that acknowledges that climate change will make droughts increasingly frequent (BBC; Il Post).

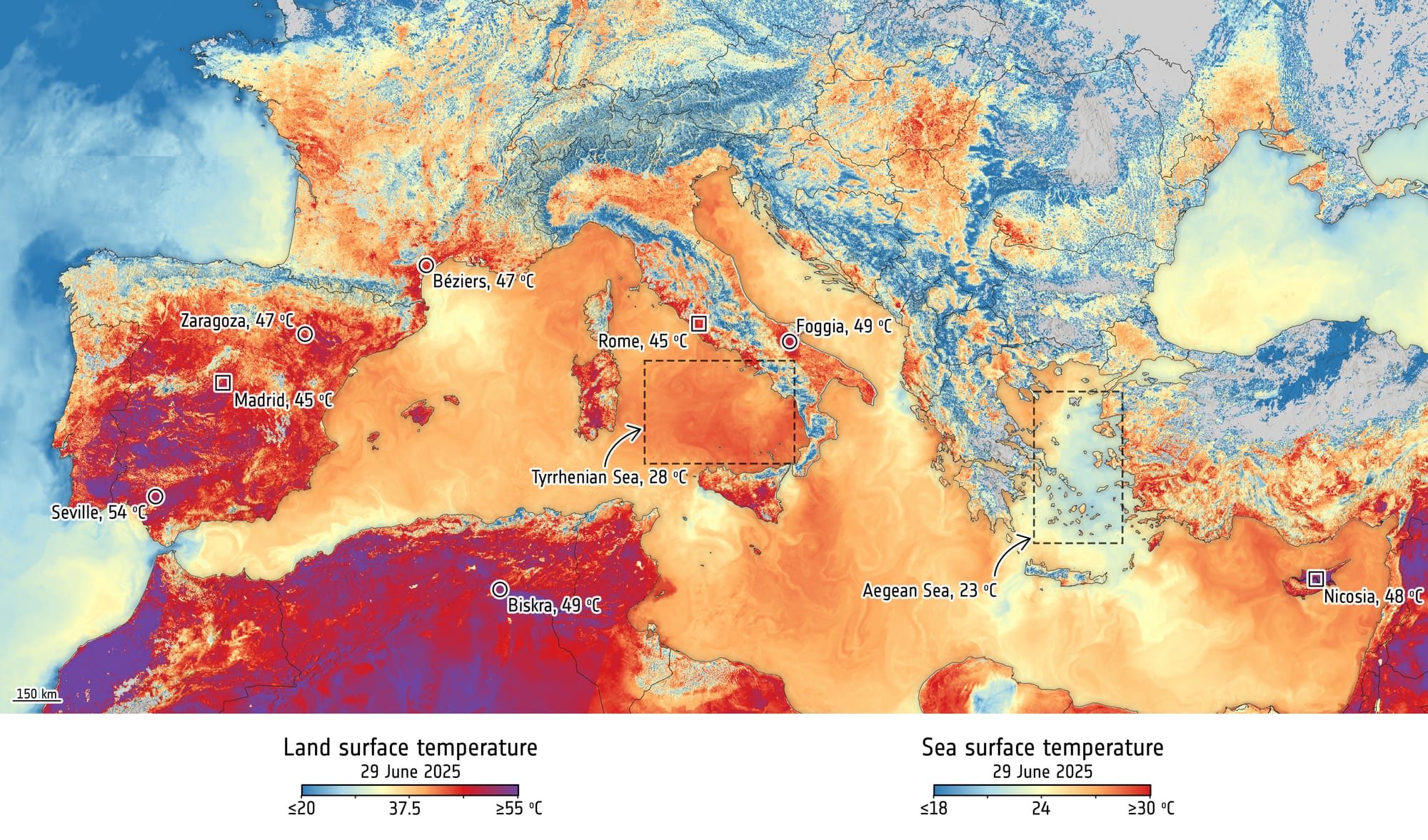

The consequences of very hot summers. Summer is now behind us and it is time to take stock. According to British scientists, the extreme heat of the past season — driven by global warming — may have caused at least 24,400 deaths, or roughly three times the number that would have occurred without human-induced climate change.

Their calculation compared the number of summer deaths in recent years across European cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants. The researchers estimated that without the effects of global warming, temperatures between June and August would have been about 2.2 degrees Celsius (4 degrees Fahrenheit) lower than those recorded in 2025, and consequently, the number of deaths would have been significantly lower.

Regardless of the exact figures, the analysis underscores a stark reality: Despite many measures designed to shield people from rising heat, deaths linked to extreme temperatures are expected to continue increasing as the climate warms (The New York Times).

And that’s only for 2025. Research suggests that between June and September of 2024 — among the hottest summers ever recorded — 62,775 heat-related deaths occurred across Europe, about 23 percent more than the previous year. The scientists behind that analysis caution that the real figure is likely higher, since deaths linked to extreme heat are rarely recorded as such.

“It’s similar in some ways to Covid: Heat often compounds existing health conditions, which is why older people are particularly vulnerable,” Chris Hocknell, director of the London-based sustainability consultancy Eight Versa, told Euronews. “It is not always clear whether heat stress was the direct cause of death or a contributing factor, but the statistical signal is clear; mortality spikes during extreme heat events.”

The hardest-hit country appears to be Italy, where 19,000 more deaths were recorded between June and September than during the other months of 2024. Italy is particularly vulnerable, both because of its very elderly population and because summer temperatures in cities like Rome and Palermo often reach 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) (Euronews).

Hotter summers also come with an economic cost. A recent report from the European Central Bank estimates that heatwaves, flash floods, droughts and lost productivity — particularly in the construction sector during the hottest summer months — could cost the European Union approximately €43 billion ($47 billion). This estimate does not include damages caused by wildfires. The regions most affected are Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and southern France. For Italy alone, losses in 2025 are projected to top €11.9 billion ($13 billion), potentially rising to €34.2 billion ($37 billion) by 2029 if current trends continue (The New York Times).

Speaking of productivity, many countries around the world — Med included — are increasingly restricting outdoor work during the hottest hours of the day. At the same time, cities are trying all sorts of things — from repainting surfaces to providing more shade — to limit the effects of extreme heat (The New York Times).

Limited connections. New evidence has emerged about the blackout that struck the Iberian Peninsula in April. A study by the think tank Ember highlights that the region is the most vulnerable in Europe because of its limited interconnections with the continental grid. Spain restored service after 16 hours with support from France and Morocco, while Portugal reactivated its grid in 10 hours, largely thanks to its national hydroelectric plants.

The blackout was traced to systemic failures and power surges — not cyberattacks or dependence on renewable energy. Both countries are now urging the EU to invest more in cross-border interconnections to prevent future crises (Euronews).

Egypt cracks down on hunting migratory birds. A few months ago, Lapilli highlighted an investigation into organized trips to hunt migratory birds in Egypt — birds that were later stuffed and imported into Europe via Malta, despite being protected there. In part thanks to that reporting supported by Journalismfund Europe, the Egyptian Ministry of Environment has intervened, announcing a total ban on tourist bird hunting in the New Valley Governorate for the upcoming season, which runs from October 1, 2025, to March 31, 2026. The ministry has also imposed a temporary hunting ban on Lake Nasser until January 2026. These restrictions apply to all species, both migratory and non-migratory, marking the most far-reaching government action in recent years to curb wildlife hunting and protect bird populations (The New Arab).

There are many more plants we could eat than we do. Over the past few centuries, human domestication has narrowed our food base to the point where 90 percent of our calories now come from just 15 crops. Monocultures, however, are highly vulnerable to disease and climate change, and relying on them in an unstable world carries serious risks.

With this in mind, plant conservationist Benedetta Gori and photographer Rachele Daminelli set out on a journey across the Mediterranean in search of wild plants that have sustained local communities for centuries. They catalogued 2,700 species, with a special focus on Sardinia — a biodiversity hotspot and one of the world’s celebrated “Blue Zones,” known for the longevity of its inhabitants, which many attribute to their lifestyle and diet (Imagine5).

Sentinels of a warming world. In our latest Lapilli+, science and nature journalist Roman Goergen explores the case of the Alpine marmot and how studying this species reveals the impact of climate change in the Alps. The issue is now fully accessible to all. You can find it here.

Desalination plants in Morocco. Morocco, now in its seventh year of drought, is turning to seawater desalination to secure drinking water and sustain agriculture, particularly water-intensive export crops like tomatoes, watermelons and citrus fruits. Once limited to the oil-rich Gulf states, desalination is now expanding worldwide, including in the Mediterranean, as climate change worsens water scarcity. Algeria is planning nine large-scale plants. Egypt has three in the pipeline. Jordan, one of the most water-scarce countries in the world, is preparing not only a mega-plant but also a 250-mile pipeline to deliver desalinated drinking water to its capital.

Morocco has already inaugurated a major plant near Agadir, supplying 1.6 million residents and irrigating key agricultural areas. By 2031, the country plans to host four of the world’s ten largest desalination plants to strengthen resilience and eventually power them with renewable energy.

The technology, based primarily on reverse osmosis, has become more accessible, but it comes with drawbacks. Plants discharge brine — a residue with extremely high salt concentrations — back into the sea, which can increase local water temperatures. Desalination also demands significant energy and generates greenhouse gas emissions when powered by fossil fuels.

Critics argue that Morocco’s water crisis stems not only from climate change but also from decades of political choices. Subsidies and incentives under the Morocco Green Plan encouraged large-scale cultivation of these water-intensive, non-native crops to export to Europe in arid inland regions. This strategy brought economic benefits, wealth and jobs to rural areas. Yet more efficient irrigation systems, rather than saving water, were used by farmers to expand production further. Today, agriculture accounts for about 85 percent of Morocco’s water consumption — far beyond available resources.

Experts warn that downsizing agriculture is inevitable. Desalination will never meet the 12 billion cubic meters (3.2 trillion gallons) required annually by farms; doing so would take 35 of the world’s largest plants. For now, large farms located near desalination networks are thriving, while small inland farms are uprooting orchards, selling land or switching to drought-resistant crops like cactus. Without a reduction in agriculture, desalination risks becoming little more than a costly and temporary relief — delaying, rather than solving, Morocco’s deepening water crisis (Washington Post).

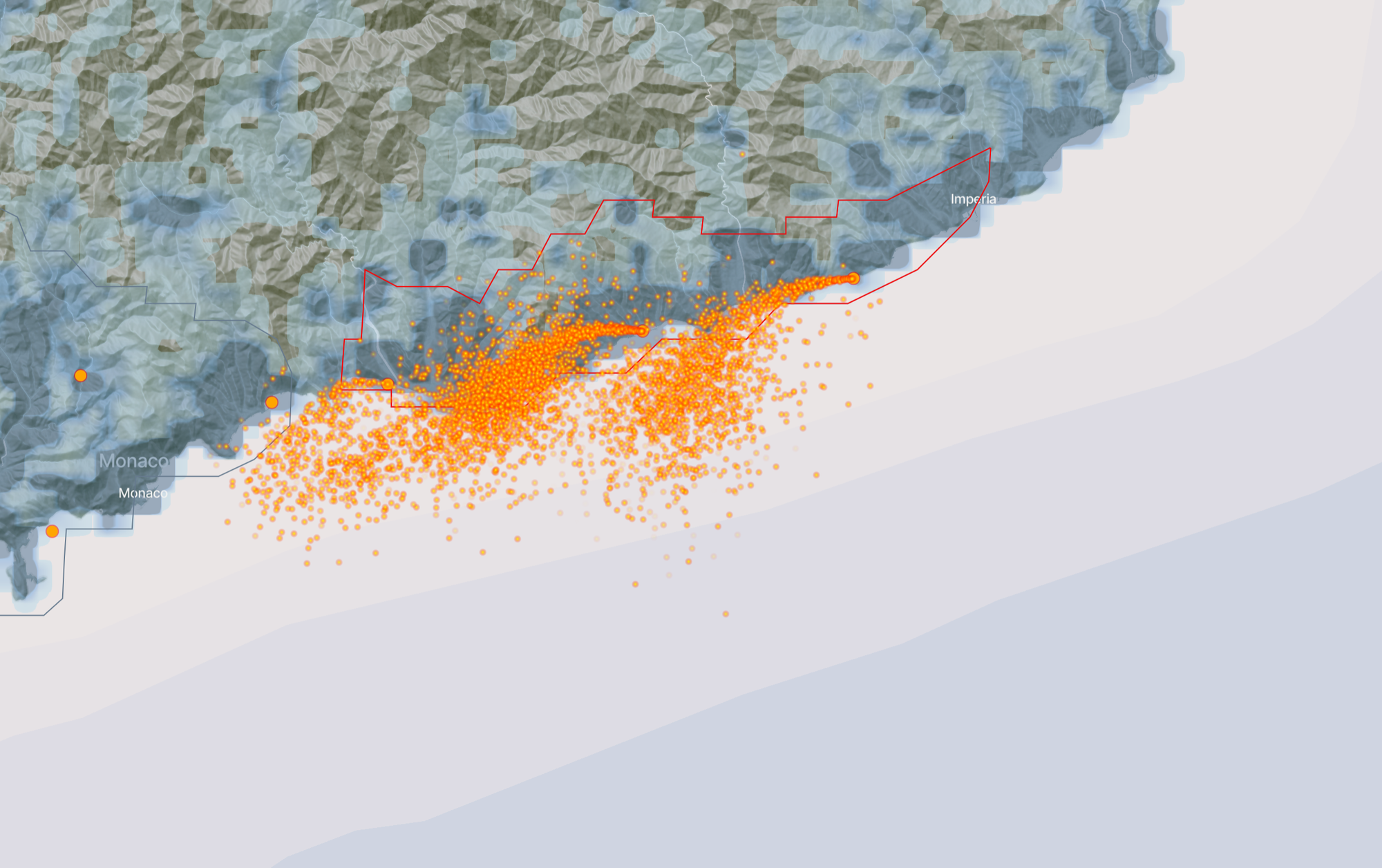

Viewing emissions. An international coalition of scientists, universities, non-governmental organizations and tech organizations has launched an interactive map that tracks air pollution’s movement through cities worldwide and pinpoints its sources. The database spans more than 2,500 urban areas and 660 million emission sources — including power plants, refineries, ports and mines — and is freely accessible.

The findings are striking: The top 10 percent of polluting facilities expose roughly 900 million people to dangerous levels of PM2.5 particulate matter, a pollutant linked to nearly 9 million deaths every year. Around the Mediterranean, many of the most polluting sources are concentrated near ports. The project’s goal, researchers explain, is to make these pollution “plumes” visible to raise awareness among governments and communities and encourage interventions to cut emissions that harm health and drive global warming (CNN).

GUGLIELMO MATTIOLI

As a multimedia producer, he has contributed to innovative projects using virtual reality, photogrammetry, and live video for The New York Times. In a past life, he was an architect and an urban planner, and many of the stories he produces today are about the built environment. He has worked with publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, and National Geographic. Born and raised in Genoa, Italy, he has been living and working in New York City for more than 10 years.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in November or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma.